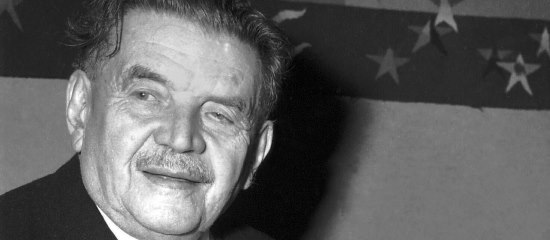

Edouard

Herriot

Former President of the French Council (Prime Minister) and Provisional President of the Consultative Assembly

Speech made to the Assembly

Wednesday, 10 August 1949

By the terms of paragraph 3 of the Agreement concluded on May 5th, 1949, between the signatories of the Statute of the Council of Europe, the Preparatory Commission which was created by that Agreement was instructed to “nominate the provisional President for the inaugural Session of the Assembly, to act until the Assembly had elected its own President; it being understood that the provisional President cannot in any case be a member of the Assembly during its first Session.”

I have been informed that the Preparatory Commission during its meeting of 12th July has been so good as to nominate me, by a unanimous vote, to discharge this highly important function. My first duty – which is at once imperative and agreeable – is to thank the ten Governments who have associated themselves in conferring upon me so high an honour. Perhaps they were moved by a desire to recompense in this way an old French Parliamentarian, who has never ceased, in spite of the harsh disappointments of events, to labour for a closer association between the peoples as is indeed attested by the draft Protocol presented to the League of Nations in 1925.

(Applause.)

At that time, and later, I had the honour of being in the confidence of Aristide Briand, whose noble features cannot fail to be recalled to our memory at this moment.

(More applause.)

He was the first statesman to proclaim the idea of an association of this character and – although this detail is merely of historical value – the European Federation held two meetings in Geneva.

It is with all the authority of that great name and with sincere emotion that I now greet you, dear colleagues, and in your persons, I pay homage to your countries. It is a mistake, in my view, to believe that an international “rapprochement” must have its origin in a diminution of the idea of patriotism. The loftiest sentiments supplement, rather than conflict, with one another. The best citizen is one who, in the first place, shows his profound attachment to his family, and it is be' cause of the deep devotion that he feels to his own nation that he will manifest a sincere respect for the genius of other peoples, as evolved by nature and by history.

You have present among you, dear colleagues, the very best examples of that richness of the soul which reconciles, rather than opposes; and for that reason, you will allow me to offer our common homage to one to whom every free man owes so deep a debt – my illustrious friend, Mr Winston Churchill, (Loud applause.) who has shown us to what heights human energy is capable of attaining. For in many moments of deep tragedy he bore upon his shoulders the whole weight of the world crying out for help. From his mind sprang the movement which has brought us together here.

Your Statute has instructed you to “give form to the aspirations of the peoples of Europe” and to “furnish the Governments with the means of keeping constantly in touch with European public opinion”. There is no question, in any way, of organising or preparing a military alliance; it is simply a question of “safeguarding and realizing the ideals which are the common heritage of the participating Members”.

We are not declaring war on anyone. Whatever may be alleged, our meetings have no aggressive intentions towards anybody. “All the doors”, as M. Schuman has said, “are open towards the East, towards all those who today refrain from taking their place among us.”

We merely desire to associate ourselves in order to defend these two great acquisitions of human civilisation: freedom and law. Freedom: for which so many men have sacrificed themselves and which requires that, in every collective organisation, the individual shall retain the government of his own conscience and his own personal and moral individuality; and Law: which, by agreed rules, sets limits to the interest and privileges of the individual.

It shall not be said that this is a dream. As early as the eighteenth century, under the inspiration of a number of English, Italian and French thinkers, a strong current of liberalism was flowing through the countries of Europe.

Voltaire, in his philosophic dialogues, wittily defended the necessity of what he called “mutual aid”.

Suppose, he said, that two old cardinals were to meet, starving and dying of hunger underneath a plum tree. Would they not help each other to climb the tree and gather the plums?

Even sovereigns who were most inclined to despotism such as Catherine II and Joseph II, welcomed the reforms that were inspired by this new spring-tide. The revolutions of 1848 gave a great impetus to fraternity. Now, more than ever, a closer association of Europe seems a matter of urgency.

My friends, these facts, as well as our moral obligations, compel us to accept this rapprochement.

That has been said over and over again, but is a truth which needs to be reiterated, so that it sinks into the public conscience. The problem which you are going to examine is, for Europe, a problem of life and death.

As early as 1920, a professor of the Sorbonne, Albert Demangeon, in his work Déclin de l’Europe, called attention to the shifting of the world’s centre of gravity as a result of armed conflicts, the opening up of new routes, the accumulation of fresh capital and the general extension of the industrial regime.

The world has evolved, fearfully. The two world wars, because of the immense sacrifices in men and money which they cost Europe, sharply accentuated this shifting of values.

Europe, which absorbed raw materials in order to re-export them as manufactured products, now finds itself encircled by young nations which have adapted themselves to an industrial life and are restricting their purchases, facing us with the problem of cost prices and obliging us to change our own systems.

In his work:

Paul Valéry criticises our continent for having failed to organise the rest of the world for the purposes of Europe, for having only been able to repeat its past and for losing its way in quarrels about villages, church towers and shops.

“These wretched Europeans”, he says, “preferred to play at Armagnacs and Burgundians instead of assuming in all parts of the world the grand role which the Romans knew how to play and maintain for many centuries in the world of their age... Europe will be punished for her politics; she will be deprived of wines, beer and liquors... and of other things as well.”

That prophecy dates from 1917. Europe, according to Valéry, had developed her spiritual liberty to the extreme; she had built up a capital of very powerful laws and procedures, and yet her policy continued to be empirical and summary.

Let us face facts. As a result of the Marshall Plan were are now living under an artificial regime in a temporary state of well-being.

The trade figures between the States of Europe are dramatic. They are expressed in dollars, which are not exactly comparable, since the United States from 1933 onwards experienced a devaluation as a result of the grave economic crisis of 1929, as well as a considerable rise in the cost of commodities resulting from the war. These figures are none the less interesting because they serve to illustrate the disequilibrium of commercial exchanges.

The value of the goods sold by Europe to the United States averaged 1,200 millions dollars over the years 1926-1930, amounted to 600 millions in 1938 and 1,100 millions in 1948. For the same periods, Europe’s purchases from the United States amounted to 2,200 million dollars, 1 milliard 300 millions and 4,800 millions.

Before the war, Europe was able to meet the deficit in commercial exchanges from resources other than exports to the United States, but today this is no longer possible.

A remedy must be sought at once for such a situation.

It is true, as has been said, that the experiments made recently to harmonize the economies of different countries have hardly been encouraging.

Various explanations have been given for these setbacks, but the real reason, in my view, for this disappointing result is that the problem has been tackled within the framework of existing institutions and subject to all their complexities.

Aristide Briand expressed this emphatically, in his speech of 5th September 1929, to the League of Nations, when he said: “The Governments will succeed in solving the problem only if they tackle it themselves and deal with it from a political point of view. If they leave it on the technical plane, they will find all the special interests roused against them and combining in order to oppose them.” In order to get over so many difficulties and remove them, there must be a political body, a political will and political action. This is the reason and the meaning of your gathering.

This is an event of cardinal historical importance. Your task is to succeed, through the efforts of all, in a field where so many half-hearted efforts have failed.

Your programme has numerous aspects: social, cultural, legal, administrative. Since it is essential for you to interest the great mass of the people in your work, you will doubtless devote an important part of it to social questions and to all matters concerning the improvement of worker’s conditions.

It is for you to decide whether you intend to debate in this first Session the aims of your gathering. Numerous problems will come up for your consideration: the organisation of large-scale European public works, the reorganisation of trade, or, in the cultural field, the question of the inter-validity of university degrees, a matter of the gravest importance to our younger generation. But it is you yourselves who must decide on the order and the nature of your work. I must conclude and not trespass on the field of your Bureau.

I do feel however, that I ought to touch on one question which is extremely delicate.

On the question of Germany, it is best to be quite honest. Mr Bevin recently touched on this problem in the House of Commons with his usual wisdom. On this grave question, our minds are divided. On the one hand we are well aware of the immense contribution which Germany has made to science, letters, the arts, and to progress in all fields. She gave to the world Emmanuel Kant and his idea of everlasting peace; the man who, in defence of Human Rights, wrote the admirable phrase, “Politics must bend the knee to morals”. Goethe is an example of an intelligence which goes beyond and rises above all frontiers. To the very sound of the cannon at Jena, Hegel was teaching us that the mind, science and civilisation must triumph over the misadventures of the world, over its prejudices and the humiliating slavery of its past. To the greater glory of human brotherhood, Beethoven composed a brilliant work the emotional power of which is inexhaustible. If Germany had remained faithful to these great examples, how eagerly we should work with her for the organisation of a liberal Europe!

But we, who are representatives of, and, to a certain extent, responsible for many human lives, are horrified to note the reappearance of certain ideologies based on the cult of force and on the right of the mailed fist. On several occasions they have led, to an extent never known before, to massacres, torture, executions, deportations and the horror of the gas chambers. Many families in Europe mourn innumerable victims. It is therefore for Germany herself to reply to a question which for us, raises a moral, even more than a political, problem.

And now, Ladies and Gentlemen, you are about to start on your work. You have first to set up your organisation. The Council and the Assembly of Europe must have a permanent character. Right from the outset, you know that you are acting as individuals, not subject to any pressure. This is in line with the ideas of Freedom and Law. Any act of creation, even the birth of a child, contains a certain risk; any act of creation is an act of faith. The European Assembly will be what your determination makes it. It has the honour of meeting in Strasbourg, in the country where the Marseillaise was born; in this beloved town with the faithful heart, which has so often been martyred but has never lost its faith. You are meeting on the banks of the Rhine – “the river which remembers”, as Barres called it. In earlier times, we came here secretly, in hiding, in order to exchange with our friends whispered words of encouragement and hope. How proud we are today to see here the free meeting of this illustrious Assembly to which the fate of Europe is committed.

My dear friends it will be the greatest honour in my life to have presided over your gathering for one day. I hope I have made you feel the depth of my esteem for you as individuals, and, through you, for your countries. When I leave you, I shall remain among you in spirit, in the certainty that you will work with all your hearts in order to make a reality of the greatest ideal which has ever been put before people of all convictions and of all beliefs, “Peace on earth to men of good will”.

(Prolonged applause.)