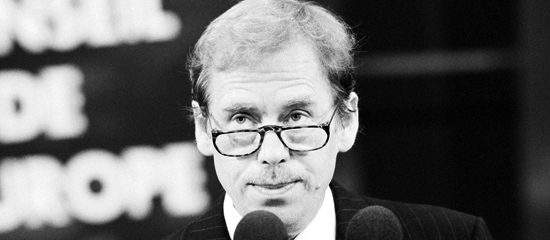

Václav

Havel

President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic

Speech made to the Assembly

Thursday, 10 May 1990

Mr President, Madam Secretary General, Ministers, ladies and gentlemen, the twelve stars in the emblem of the Council of Europe symbolise – among other things – the rhythmical passage of time, with its twelve hours in the day and twelve months in the year. The emblem of the institution in which I now have the honour of speaking strengthens my conviction that I am speaking to people who are acutely aware of the sudden acceleration of time that we are witnessing in Europe today; people who understand someone like myself who not only wants time to go faster but actually has a duty to project this acceleration into political action.

If you will bear with me, I shall once again try some thinking aloud on this subject in a place that is perhaps the environment best suited to such reflections.

Let me start with my personal experience.

I see these twelve stars as a reminder that the world could become a better place if, from time to time, we had the courage to look up at the stars.

Throughout my life, whenever my thoughts have turned to social affairs, politics, moral questions and life in general, there has always been some reasonable person ready to point out sooner or later, very reasonably and in the name of reason, that I should be reasonable too, cast aside my eccentric ideas, and acknowledge that nothing can change for the better because the world is divided once and for all into two worlds. Both halves are content with this division and neither wants to change anything. It is pointless to behave according to one’s conscience because no one can change anything and those people who don’t want a war should just keep quiet.

I often had to listen to this “voice of reason” following Brezhnev’s invasion of Czechoslovakia, after which all the so-called “reasonable” people felt much revived because it had given them a new argument for their indifference to public affairs. They could say: “There you are, that’s the way it goes, they’ve written us off, nobody cares, there’s nothing we can do about it, it’s no use trying, so just learn your lesson and say nothing! Or do you want to go to jail?”

Naturally, I was by no means the only one to disregard this wise advice and to continue doing what I considered to be right. There were many of us in my country. We were not afraid of looking like fools, but went on thinking about how to make the world a better place and we did not hide our thoughts. Our efforts eventually merged into a single coordinated flow which we called Charter 77.

All of us together in the charter, and each one of us individually, thought about freedom and injustice, about human rights, about democracy and political pluralism, about market economics and much else besides. Because we thought, we also dreamed. We dreamt, whether in or out of prison, of a Europe without barbed wire, high walls, artificially divided nations and gigantic stockpiles of weapons, of a Europe free of “blocs”, of a European policy based on respect for Man and human rights, of politics unsubordinated to transient and particular interests. Yes, the Europe of our dreams was a friendly community of independent nations and democratic states. When I had the chance to snatch a quarter of an hour’s conversation with my friend Jiri Dienstbier (now Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs) as we changed machines at the end of a shift in Hermanice prison, we sometimes dreamt of these things aloud.

Later, when he was working as a stoker, Jiri Dienstbier wrote a book called Dreaming of Europe. “What sense is there in a stoker writing down Utopian notions about the future when he can’t exert the tiniest influence and can only bring further harassment upon himself?”, wondered the friends of reason shaking their wise heads.

And then a strange thing happened. Time suddenly accelerated and what previously took a year suddenly happened in an hour. Everything started to change at surprising speed, the impossible suddenly became possible and the dream became reality. The stoker’s dream became the daily routine of the Minister for Foreign Affairs. And the advocates of reason are now split into three groups.

The first is quietly waiting for setbacks to occur which will serve as yet another argument in support of the nihilistic ideology. The second is looking for ways to push the dreamers out of government positions and replace them again by “reasonable” pragmatists. And the members of the third group are loudly proclaiming that what they have always known would happen has come to pass at last.

I am not telling you of this experience to ridicule my allegedly reasonable fellow citizens, but for a very different reason: to show that one is never wrong to think about alternatives, however improbable, impossible or quite simply fantastic they may seem at the time.

We don’t dream, of course, just because the results of our dreams might come in handy one day; we dream, as it were on principle. Apparently, however, there can be moments in history when the fact of having dreamt “on principle” may suddenly prove useful.

Time flies. It is flying as I speak. I shall therefore not detain you any longer with literary considerations but will come to the point.

First a few words about my country.

Following the attack against the students on 17 November 1989, the patience of our two nations finally gave out and we quickly overthrew the totalitarian system which had dominated our country for forty-two years. We have set out on the path to democracy, to political pluralism and market economics. The press in our country is free and in a month’s time we shall have our first free elections for forty-two years, with a broad range of political forces taking part.

I am quite convinced that these elections will stand the test even in the eyes of all foreign observers. In our country, there is freedom of thought and freedom of religious belief; for the first time since the second world war, all the Catholic dioceses have their bishops; religious orders are functioning again. Our country has no state ideology. The only idea which it wants to instil in its domestic and foreign policy is respect for human rights in the broadest sense, and esteem for the uniqueness of every human being.

Our parliament has adopted, among many other laws, some important economic legislation to assist the transition to a market economy and give human labour back its meaning. We are preparing democratic constitutions for our federation and for both national republics. We want at last to give full legal expression to the identity of our two nations and safeguard the collective rights of our national minorities. We feel we are a sovereign state and we want to live in friendship with all nations but we are determined to defend our sovereignty if need be.

I consider that we are entitled to special guest status with your Assembly and I thank you on behalf of our people for granting it three days ago. It is my earnest hope that the Council of Europe will view our application for full membership sympathetically.

What I have told you of my country does not mean that Czechoslovakia today is an oasis of harmony. Far from it. We are going through one of the most difficult periods in our recent history. We are submerged by enormous problems which were previously latent and have only just come to the surface following our newly won freedom. What we have inherited from the former regime is a devastated landscape, a disrupted economy and, above all, a mutilated moral sense.

The overthrow of totalitarian power was an important first step but it was only the beginning of our journey on which we shall have to make rapid progress with many more pitfalls ahead.

We find that there is almost nothing we are good at and much that we have yet to learn. We must achieve political maturity, independence of mind and responsible civil behaviour. We are well aware of this, perhaps more so than many who watch us from afar with concern and despair at our clumsiness.

I am not saying all this to gain undeserved advantages or even compassion but because I am accustomed to telling the truth, even in a situation where it might seem more advantageous for me and my fellow citizens to lie, or at least to say nothing. It is my opinion that a clear conscience outweighs all other advantages.

Now that I have briefly acquainted you with my country, I can at last start my thinking aloud about the Europe of today and of tomorrow. These thoughts won’t be just a re-hash of a dissident’s former dreams, but will reflect what I have learnt since taking office, from my many conversations with foreign statesmen.

I think it would be pointless to repeat what everybody knows, namely that today unprecedented prospects are opening up for Europe, not least the possibility of becoming a continent of peaceful and friendly co-operation.

I will therefore move straight away to some specific measures in the sphere of structures, institutions and treaties which it would be necessary to implement, at once or in some agreed sequence, for the newly emerging hope to become a reality. I shall start from the assumption that the structures born of the old system should either be smoothly transformed or merge into new structures, or simply be abolished and left to wither. Entirely new structures should be created in parallel as starting points or seeds of a future order.

For the sake of clarity, let us divide this whole sphere into four categories, that is to say security, political, economic and civic structures, institutions or mechanisms.

The post-war division of Europe in the security and in the military sphere is enshrined in two treaties, namely the Atlantic Alliance and the Warsaw Pact. These are military groupings which differ notably in character, history and vocation.

Whereas NATO was set up as an instrument of defence for the Western European democracies against the danger of expansion by the Stalinist Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact was conceived as a sort of offshoot of the Soviet army and an instrument of Soviet policy. The aim was to declare the satellite status of the European countries over which Stalin had gained control after the second world war.

If we then consider the geopolitical context, where the Western European democracies adjoin the ocean to the West and the former Soviet satellites border upon the Soviet Union to the East, we can easily grasp the asymmetry of the whole situation.

In spite of this, I believe that in this radically new situation both groupings should gradually move towards the ideal of an entirely new security system, foreshadowing the future united Europe: this would provide some sort of security background or security guarantees. It would be a kind of security community involving a large proportion of the Northern hemisphere.

Thus the guarantors of the process of unification in Europe would have to be not only the United States and Canada in the West, but also the Soviet Union in the East. When I speak of the Soviet Union I am thinking of the community of nations currently in the making in that country.

What does this specifically imply for NATO and the Warsaw Pact in the light of the aforementioned asymmentry?

For both alliances it implies that the function they already fulfil to some extent, that of political instruments in joint disarmament negotiations, should be strengthened while their former role as instruments of defence of one half of Europe against possible attack by the other half should be played down considerably. In brief, both alliances should function more clearly as instruments of disarmament rather than instruments of combat.

It seems that NATO, being the more meaningful, more democratic and more effective structure, could become the seed of a new European security system more readily than the Warsaw Pact. But it, too, must definitely change. Above all, in the face of today’s reality, it should transform its military doctrine. It should also – in view of its changing role – change its name without delay. There are at least two reasons for this: firstly, contemporary changes are the result of the victory of historical reason over historical absurdity and not the result of a victory of the West over the East; the present name is so closely linked to the cold war era that it would be a sign of a lack of understanding of present- day developments if Europe were to unite under the NATO flag. If the present structure of the Western European security alliance becomes the precursor or embryo of a future Pan-European alliance, then it will certainly not be due to the West’s having won the third world war; it will happen because historical justice has triumphed. The second reason why NATO must change its name is that the present name is geographically inaccurate; for it is clear that in a future security system only a minority of participants would border upon the Atlantic Ocean.

As far as the Warsaw Pact is concerned, it is likely that when it ceases to serve as a political instrument of European disarmament and to assist certain countries on their way back to Europe, it will lose its purpose and dissolve. What originally came into being as the symbol of Stalinist expansion will in time lose all raison d’être.

The great “Northern” security zone could rightly be called the “Helsinki” zone: this is immediately clear, as the countries which can and should belong to it are in fact the participants in the so called Helsinki process. What this implies is obvious enough. The new structures which would emerge in parallel with the transformation or gradual dissolution of the old could grow out of the foundations provided by the Helsinki process.

The Czechoslovak proposal for the establishment of a European Security Commission as the starting point of the future united “Helsinki” security system and the guarantee of a united Europe stems from this idea. The participating states in the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe have been informed of this initiative and there is no need for me to explain it again.

As the Warsaw Pact gradually faded out or lost its purpose and NATO gradually transformed itself, the significance of this Commission would grow, along with any new structures around it.

Let me try to summarise these considerations.

If the Helsinki security process were to develop from the stage of recommendations to participating states to joint treaty commitments, a broad framework of guarantees would be created for the emerging political unity of Europe.

The accelerated course of history compels us to act on every political issue immediately or within a reasonable time. I shall try to do so in this context.

It is possible – and it is to be hoped – that the summit of the participating states in the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe will be convened in the course of this year. I would like to assure those states who have suggested holding it in Prague that Czechoslovakia would regard this as a great honour and would do its utmost to ensure it success. However, what is more important than the venue of this summit are its content and its purpose. We have already suggested that it could do more than is planned in the present agenda.

In the first place, the summit could – if all participating states agreed – set up the proposed European Security Commission which could start working as of 1 January 1991. Czechoslovakia proposes Prague as its headquarters. The Secretariat, or its representative part, could have its seat in one of the beautiful Prague palaces near the Castle. Of course it would be gratifying if the first of these European institutions were to be located in Prague, but this is naturally not a precondition. Even if the summit were held somewhere else, it could still establish the institution in Prague.

If the summit is convened this year, it could decide that the conference planned for 1992, commonly known as Helsinki 2, will be held in the autumn of 1991 instead.

The third and most important decision that could be taken at this year’s summit would be a decision on the agenda and purpose of Helsinki 2 and on the immediate start of preparations, for which purpose the proposed commission could also serve. This task would be the drafting and perhaps the signing of a new generation of Helsinki Accords. These accords would break new ground by not being simply an extensive set of recommendations to governments and states, but a series of treaties on co-operation and assistance in the sphere of security. They would comprise some sort of obligation to provide mutual assistance in the event of an attack from outside and a duty to resort to arbitration in the event of local conflicts within the zone.

Clearly, such negotiations and accords could fix the present European borders once and for all and, through the system of treaties and guarantees, close the chapter of the second world war and its abominable consequences, not least the era of Europe’s prolonged and artificial division.

In conclusion, by the end of next year the foundations of a new and united “Helsinki” security system could be laid, providing all European states with the certainty that they no longer have to fear each other because they are all part of the same system of mutual guarantees, based on the principle that all participants are equal and on the duty of all states to protect the independence of each participating country.

Allow me one more remark. It concerns nuclear weapons in Europe. In the post-war period, nuclear weapons – produced never to be used – became a part of a security model which paradoxically ensured peace through the balance of terror. The nations of Central and Eastern Europe, however, paid a heavy price for the efficiency of this nuclear model by remaining in the grip of a totalitarian corset.

An excessive quantity of weapons of any type, nuclear weapons especially, inevitably disfigures the territory on which they are deployed. This applies particularly to the short-range variety which we call “tactical”.

We therefore welcome President Bush’s proposal to abandon the planned modernisation of these weapons. Should the summer NATO conference decide on the gradual elimination of other less modern missiles now deployed in Central Europe we would welcome this too.

What justification can there be for the existence of weapons which can only strike Czechoslovakia, the eastern part of Germany now in the process of unification, and possibly Poland? Whom will they deter? The new governments elected in the first free elections for decades? The new democratically elected parliaments?

As I said in the Polish Parliament, our society sometimes reminds me of newly amnestied prisoners who find it hard to adjust to freedom. People are full of prejudices, stereotypes and notions shaped by long years of totalitarianism. Can they understand the purpose of weapons targeted at them? The supporters of the former regime in our country and elsewhere are waiting for their chance. It would be a historical paradox if those who helped us in the past in our struggle against the totalitarian regime were to offer them this chance now.

In my opinion, the main disaster of our modern world has been its bipolarity, the fact that the tension between the main powers and their allies was indirectly transferred somehow or other to the whole world. This situation persists to this day.

The whole world seems constantly torn apart by this tension and stifled by the existing superpowers. The victims of this unfortunate state of affairs are above all the hundred or so states inaccurately called the Third World, the developing world, or the world of the non-aligned. Their understandable anxiety over the possibility that the emergence of a united “Helsinki” security zone could widen the gap between North and South is unjustified. The very opposite is true. It would be an important step from bipolarity to multipolarity!

In addition to the powerful North American continent and the rapidly changing and liberating community of nations of today’s Soviet Union we have the emergence of a large European connecting link. These three entities, living in peace and mutual co-operation, would indirectly open up a new chance of a full life to other countries or communities of countries.

The whole international community would start changing from an area of mutual competition and of direct or indirect expansion of two superpowers into an area of peaceful co-operation among equal partners. The North would cease to threaten the South through the export of its interests and its supremacy but would beam towards the South the idea of equal cooperation for all.

Against the broad background of this large “Northern” or “Helsinki” security zone, and simultaneously with its emergence, obstacles which until recently seemed insurmountable would fall away and Europe could quite swiftly achieve political integration as a democratic community of democratic states.

This process would no doubt go through several stages and involve a number of different mechanisms simultaneously. It may be that initially, say within five years, a community will be established on European soil that we might call the Organisation of European States, by analogy with the Organisation of American States. Then, at the beginning of the third millennium, we could with God’s help start to build the European Confederation proposed by President Mitterrand.

With the consolidation, stabilisation and growing competence of the future confederation, the whole “Helsinki” security system would gradually become redundant, and in the end Europe would be capable of ensuring its own security. At which point the last American soldier could leave Europe because Europe would have no further cause to fear Soviet military might and that powerful country’s unpredictable policy.

In my view, every move leading to this goal should be encouraged. The more varied the endeavours made in different quarters the better, because the chances of one of them succeeding will be all the greater.

Czechoslovakia therefore supports all manner of initiatives such as the small regional working groups including “Initiative 4” (Danubian-Adriatic Community), and is studying such projects as Prime Minister Mazowiecki’s scheme to set up a permanent political body of Ministers for Foreign Affairs of all European states.

You will certainly understand why I speak so extensively of these ideas, and why I do so in this Assembly, before the representatives of Europe’s oldest and largest political organisation, which has such firm, sound foundations and has already done so much useful work. Yes, the spiritual and moral values on which the Council of Europe is based and which are the common heritage of all European nations are the best of all possible foundations for a future integrated Europe.

I can see no reason why your Parliamentary Assembly and your executive bodies should not be the crystalising core of the future European Confederation. Czechoslovakia considers all the criteria for the admission of new states to the Council of Europe as excellent, recognises them unreservedly and rejoices that the Council of* Europe is responding attentively to the emerging democracies in the former Soviet satellites who are now building their relations with the Soviet Union on the principles of equality and full respect of the sovereignty of individual states.

I am firmly convinced that the day will come when all European states will fulfil your criteria and become full members. The Council of Europe was, after all, founded as a Europe-wide institution, and only the sad course of history turned it for so long into an exclusively Western European organisation.

Obviously, the states once ruled by a totalitarian system, which are now recovering from its consequences and want to return to Europe, can most rapidly and effectively do so not by competing and contending but by helping each other in solidarity. If these countries want to make overtures to the new Europe, they must first of all establish contact with each other. The new democratic government in Czechoslovakia therefore wants to do all in its power to contribute to the co-ordination of efforts by Central European countries to enter various European institutions.

That is why we so often appeal to organisations that are theoretically European, but are in fact for the time being Western only, to be more flexible in their approach for countries which for long years were severed from them even though logically they belong there.

The highest degree of integration has no doubt been achieved by the twelve countries of the European Economic Communtiy. The countries of Central and Eastern Europe, which at present are endeavouring to move from a centralised “non-economy” to a normal market economy, to enter the world of normal economic relations and to achieve the convertibility of their currencies, look to the EEC as to some distant and almost unattainable horizon.

They should therefore work together to come closer to the EEC. For its part, the EEC should create some sort of transitional ground where the economies of those states could more easily recover. This would not only be in the interests of these countries, it would be in the interests of the EEC itself and in the interests of an integrated democratic Europe.

The harsh lesson of a totalitarian system has taught us to respect human and civil rights and it is not by chance that the emerging democracies have sprung for the most part from independent civic movements, of which the Czechoslovak Charter 77 is an example. We do not forget the soil on which we grew up, or the principles that governed our struggle for freedom. We therefore realise how indispensable it is that all the efforts made by states, governments and parliaments for integration should be accompanied or even inspired by parallel efforts on the part of citizens.

This is why I spoke recently, together with Lech Walesa, in support of a European Civic Assembly. I trust that the Western European governments will also consider this plan sympathetically.

I think I should mention, in conclusion, two topical subjects that interest the whole world and are closely related to the future of Europe.

The first is Germany.

We have already formulated the Czechoslovak viewpoint, but I will repeat it. It was always clear to us that the artificially divided German nation would one day unite as a single state.

There were times when such a view – publicly proclaimed – sounded like deliberate provocation, and was considered as such by many Germans.

We are glad, not only because we deplore the artificial division of any nation, but also because we see the collapse of the Berlin Wall as signifying the collapse of the whole iron curtain and hence as a liberating phenomenon for us all.

As we have said time and again, the unification of Germany in a single democratic state is not an obstacle to the European unification process, but a driving force.

Our thoughts and actions leading to the construction of a new European order should keep step with the unification of Germany. Hence we welcome the so-called “4 plus 2” negotiations. At the same time, we fully understand our Polish brothers’ concern over the western border of their state. We consider this border as final and support Poland’s right to participate in all negotiations concerning its borders.

Such negotiations could, in our view, wind up at the Helsinki 2 conference, which should not only formally reaffirm Europe’s present frontiers, as was the case at the first Helsinki conference, but provide legal guarantees as well.

The second subject – a highly topical one – is the future of the Soviet Union.

Czechoslovakia unreservedly recognises every nation’s right to independence and to the free choice of its state and political system. I am convinced that the process of democratisation we are witnessing in the Soviet Union is irreversible. I am convinced that all the nations of the Soviet Union will peacefully move to the type of political sovereignty they desire and that the Soviet leadership will give free rein to this development before it is too late, that is before there is any threat of violent confrontation.

Apparently the time is not far off when some republics will become completely independent and others will establish a new type of community either confederative or of a looser type.

In my view there is no reason why, against the background of an extensive “Helsinki” security system, some or all of the European nations of the present Soviet Union should not at the same time be members of a European confederation and of some form of “post-Soviet” confederation.

The present Soviet leadership, which claims an affinity with the scientific conception of historical processes, undoubtedly understands the natural aspiration of all nations to independence and the artificiality of the present structure of the Soviet state inherited from the Tsarist and later the Stalinist hegemony. For all these reasons, we believe that the West should at last rid itself of its traditional fear of the Soviet Union.

One can hardly admire Mr Gorbachev and at the same time live in fear of him. We cannot endlessly brandish the spectre of conservative forces or hawks waiting to overthrow Mr Gorbachev and return the Soviet Union to the fifties. Still less can we cultivate this spectre simply to keep the armament industry in business. There is no turning back, and the future of the world is no longer determined by one man. Nor is it in anyone’s power to stop what has now become the inexorable course of history.

In conclusion, allow me to mention an anxiety we frequently encounter nowadays: the fear of national, ethnic and social conflicts breaking out in the Central European arena as a consequence of long-latent, unsettled problems. This fear prompts the question: might not our part of Europe soon become a Balkan-type powder keg?

It is our duty to rule out any such threat and to dismiss such fears as groundless. It is above all the duty of the countries of Eastern Europe to proceed with speed, co-ordination and full mutual understanding towards the solution of inherited problems. But it is also the duty of the Western European countries to give us all their help and support in this complicated process.

Ladies and gentlemen, in 1464 the Czech King George of Podebrady sent a momentous message to Louis XI, King of France, proposing that he preside over a league of peace and convene Christian rulers to a convention, which on the basis of binding international law would prevent war breaking out among members of the union and ensure their common defence.

It is surely no accident that one of the first major attempts to achieve peaceful unification in Europe originated in Central Europe. As a traditional crossroads of all European conflicts, this region has a particular interest in European peace and security. I am happy to have been able to speak of these matters here in Strasbourg, a place which was formerly the symbol of traditional conflicts, but is now a symbol of European unity.

Honoured by this chance to speak in front of the most important European political forum, I have naturally given prominence to considerations regarding political structures, systems, institutions and mechanisms. This does not mean that I am unaware of the obvious – namely that no truly new structures can be set up or existing structures substantially altered without radical changes in human thinking and behaviour and social awareness. Without courageous people, courageous structural changes are impossible. .

This remark brings me back to what I said at the beginning about dreams. Everything seems to indicate that we must not be afraid to dream of the seemingly impossible if we want the seemingly impossible to become a reality. Without dreaming of a better Europe we shall never build a better Europe.

To me, the twelve stars in your emblem do not express the proud conviction that the Council of Europe will build heaven on this earth. There will never be heaven on earth. I see these twelve stars as a reminder that the world could become a better place if, from time to time, we had the courage to look up at the stars.

Thank you for your attention.

(President Havel received a long, standing ovation.)

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you very much, President Havel. You have a marvellous career behind you – from dissident to President in a very short time. You have talked about dreams and courageous people. You, together with your Foreign Minister, Mr Dienstbier, who is also in the Assembly today, belong to the courageous people who have changed your country. We share your dreams about a new Europe.

Thank you, President Havel, for your interesting speech. Many questions have been tabled and I propose to handle them in the Assembly’s normal way. I shall invite you, President Havel, to answer each question in turn, and I shall then ask the member concerned to ask a brief supplementary question, which must not last for more than half a minute.

No fewer than twenty-three questions to President Havel have been tabled. I shall try to get through as many of them as possible. I have looked carefully at the subjects that have been given to the Table Office and I assure colleagues that I shall do my best to call them to ask questions in an order that reflects a fair balance between subjects, countries and political interests.

I begin by calling Mr Baumel to ask his question about the Assembly and a common European home.

Mr BAUMEL (France) (translation)

Mr President, we have heard your magnificent speech with immense interest and great respect. You did not elude any of the major problems. All of us, on every side of the House, are intensely aware of the historical significance of the moment we have just experienced and are deeply moved to see you here, addressing this great European Assembly.

May I ask you one question concerning the Czechoslovak Government’s proposal for a European Security Commission, of which you spoke?

Your Government says, very wisely, that the construction of a modern security system cannot dispense with the experience acquired by the organisations that already exist for the purpose of cooperation, such as the Council of Europe.

Do you consider that the experience which the Council of Europe has accumulated over the year, not least with regard to human rights, the rule of law and pluralist democracy – all of which are enshrined in the Council’s Statute – could enable our Organisation to become the indispensible parliamentary instrument of European construction in the future?

You spoke about European co-operation and possible developments after the CSCE: how do you see the position of the Council of Europe in relation to the CSCE process?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that he did not see the Council as an appropriate institution for military matters. He was confident that the commission proposed by the Czech and Slovak Government would produce the seeds of a new security system in Europe.

Mr PANGALOS (Greece) (translation)

Mr President, those among us who, in 1968, that terrible yet glorious year, refused to accept the “obvious”, that is to say the idea that reason and intelligence must yield to mechanised violence and the future be held hostage by the present, are happy and proud to see you among us.

It is no accident that you represent Czechoslovakia, a free country at last. And it is no accident that you enjoy honourable renown throughout the world. But as you know, the sun sometimes shines so brightly that it hides the stars. And yet they are there and some say their numbers are increasing constantly. I should like, therefore, to ask you the following question: How are the Czech and Slovak democratic institutions likely to develop? Do you favour a parliamentary system with a wider spread of political parties and greater emphasis on their role, or a presidential system? If I may be somewhat impertinent, do you see yourself as President of a presidential republic or even – after all, why not? – as head of a party?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that the Czech and Slovak Constitution would be finalised in two years’ time. He envisaged limitations being placed upon the powers of the President; he did not favour a French or American type of system. Forty days after this year’s parliamentary elections, presidential elections would take place. In the short term, a strong presidential function was required to oversee the development of a new federal structure in the country and the redistribution of certain centralised powers between the two republics. Candidates for the presidency were put forward by political groups, and whoever was elected would only be in office for the period leading up to the finalisation of the new constitution.

Mrs HOFFMANN (Federal Republic of Germany) (translation)

Mr President, as a German who was born in Prague and who loves her native country, please allow me to thank you most warmly for your magnificent speech and for the hand that you have stretched out in forgiveness to we Sudeten Germans. I know what terrible things were done to Czechs and Slovaks under the Third Reich and, unfortunately, I myself lost three close German relatives in May 1945 in Prague. I therefore know how essential it is that a man who is as important as you are stretches out a hand in forgiveness, a hand that we Sudeten Germans will certainly be very pleased to grasp, because it forms the basis for genuine reconciliation. I would like to ask you, Mr President, what is your view on coexistence among Czechs, Slovaks and Germans, including Sudeten Germans, in Europe in the future?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that they would succeed in guaranteeing the identity of the two nations and he hoped they would ensure the rights of minorities. He hoped that in the future borders would become largely symbolic.

Mr KORITZINSKY (Norway)

You have just reminded us that dreams and ideals are the engine of political change and that politics in a deeper sense is about making the impossible possible. During the present European development, some of the Third World countries are struggling with the challenges of making what today seems impossible possible – tackling poverty, social injustice and price mechanisms in world trade, so that human rights can be realised in the Third World.

I should like you to comment on those issues because Europeans must not forget that the money we can save from arms spending could be used to make us even richer or to operate a policy of solidarity with the Third World. Some Western European countries are now tending to cut development aid. We are making very slow progress in the negotiations between the North and the South on making world trade fairer. I should like your comments on those global changes.

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

replied that if the two blocs disarmed, more resources would be available for the Third World. Western Europe should not export weapons to the Third World in such quantities as was currently the case.

Mr COLOMBO (Italy) (translation)

Mr President, in your statements you make frequent reference to cultural and spiritual values in politics. Your meeting with his Holiness John Paul II was much noted.

Do you consider that the cultural and political advancement of the West, founded on Christian humanism, respect for the individual, solidarity and a socially oriented market economy is an adequate basis for a modern political scheme forming an alternative both to collectivist Marxism and to capitalist liberalism?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said he hoped they could free themselves from using “pigeonhole” ideologies such as Marxism and capitalism.

He wanted a system that was fair and had a social conscience and did not mind what label was attached to it.

Mr MIVILLE (Switzerland) (translation)

Mr President, previous Soviet domination in Eastern Europe was an intolerable dictatorship. It simply suppressed certain problems which are causing us trouble today. These problems are now breaking out in a way which concerns us. I mean the new upsurge of nationalism, clashes between peoples within one and the same state, the treatment of minorities and what are really racist movements, like Pamyat in the Soviet Union; and racism always implies anti-Semitism. Do you also regard this as a phenomenon which should cause us concern and what precautions are the governments of what were previously the socialist countries taking against it?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that it was understandable that there had been an explosion of national sentiment after years of suppression and there were people who thought that they could now get away with any kind of behaviour. It was difficult to counter the phenomenon of racism but he thought it would pass.

Mr LOPEZ HENARES (Spain) (translation)

Mr President, may I say how happy we are to see you among us. You personify the fight for the supremacy of reason of which you spoke.

You have more or less answered the question that I wish to ask, because you have stated that you will have a constitution in two years’ time. In the meantime, however, what measures do you propose to take with your Government to guarantee the rights and freedoms of which the Czechoslovak people are in need?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

replied that it was not an easy task because they had to reconstruct the state completely and redefine its organs but he thought they would succeed within two years. They had a draft constitution and Parliament had got through a great deal of work. Pluralism needed time to mature and parties needed time to develop their programmes. He expected that when further elections were held at the end of the two-year period they would be contested by mature parties.

Mrs VERSPAGET (Netherlands) (translation)

Mr President, you spoke in glowing terms about the importance of human rights and the realisation of collective rights for minorities. Following on from those remarks, I should like to ask you a question about the minority group which is the second largest in terms of numbers in Czechoslovakia, namely the gypsies, of whom there are nearly half a million.

Are you ready to support the idea that this group should have the right, like the other minority groups, to be defined in the constitution as a national minority, so that it can benefit from the possibility of exercising its cultural rights?

Are you ready to repeal the discriminatory legislation which is still in force in Czechoslovakia – for example, Law No. 74 of 1958?

Do you also intend to put an end to the discriminatory treatment of gypsies, as exemplified by the specific large-scale application of the legislation on sterilisation to gypsy women, who are put under moral pressure by the social services to undergo sterilisation?

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

agreed that there was discrimination and hoped that the problem would be solved. Recent racist demonstrations against gypsies had been organised by people wishing to confuse the issue. Events had possibly been exaggerated. There were already gypsy initiative parties and they would participate in the election.

THE PRESIDENT

According to the timetable and President Havel’s hectic programme, we should have finished by now. Nevertheless, I shall allow two more questions. Then we must finish to make it possible for President Havel to complete his other activities. I call Mr Altug.

Mr ALTUG (Turkey) (interpretation)

recalling that it was primarily President Havel and other intellectuals who had started the democratic reform process asked what political views, Christian, socialist or liberal would emerge victorious in the forthcoming election and how did he see the role for Charter 77.

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that Charter 77 was a movement, not a political party, which had been established to defend human rights. It had not lost its significance. It was mentioned every day and pointed to crises arising from violations of human rights. The day before, it had produced a document on racist demonstrations. In his country, political associations sprang up quickly, from left to right, as renewal took place after a long interruption.

Those political forces were latent and therefore terms were confused as between right or left. Civil Forum was seen by opinion polls as most likely to emerge as victor of the election.

Mr SARTI (Italy) (translation)

Mr Havel, last year the best-seller in European bookshops was your valuable little work on the destiny of words. My question is whether today you would be able to write another such book on the fate of the word “communism”.

Mr Havel, President of the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (interpretation)

said that the text was not really a book. It had been written for a conference. As for “communism” he really did not know what it meant and therefore tried to avoid the word. If he were to write a sequel, subsequent to the changes, he would probably write about the way words such as democracy, liberty and human rights had been abused. He would try to examine the true meaning of these terms.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you very much, President Havel. That concludes the list of questions.

The standing ovation that you received, President Havel, when you finished your speech says far more than I can express about the sympathy that we feel for you and your colleagues here today and for your country. Therefore, I shall end by thanking you once again for coming to Strasbourg as the first ever head of state from your country. We wish you and your country all the best in future.