1. Introduction

“…Africa, the biggest moral cause, I think, in the world today…”

(Tony Blair, then British Prime Minister, speaking to CNN at the

Davos World Economic Forum, 2007)

1. Half way into the time frame

the international community has set for itself to achieve the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs) there is broad consensus that much more needs to be

done. According to the United Nations, it is not unlikely that none

of the internationally agreed goals for poverty reduction will be

met for the African continent. While some progress has been made

so far on education and poverty reduction, the political commitment

of African leaders and of the international community needs to be

sustained and increased in order to speed up progress for improving

the living conditions of millions of Africans.

2. NEPAD was launched in 2001 and has prominently been endorsed

by African countries and their partners in industrialised countries.

It builds on the premise that Africans bear the primary responsibility

for the development of their continent and subscribes to achieving

the MDGs. On the basis of African ownership and commitment, a renewed

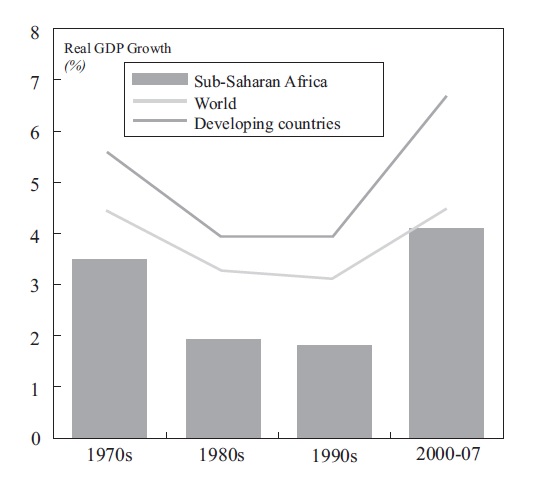

form of partnership with the international community has been defined.

While African leaders promised to improve governance structures

and to take charge of the development process, the international

community pledged to increase its financial contribution and its

commitment to making aid more effective. The terms of this new form

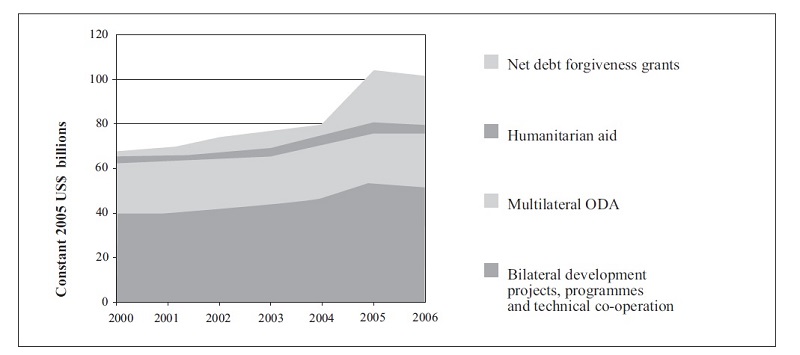

of co-operation were endorsed in the 2002 Monterrey Consensus and

the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.

3. It is widely acknowledged that good governance is a key element

for successful social and economic development. Parliaments are

a necessary actor to ensure good governance through their functions

in legislation, oversight, and representation, as well as through

their budgetary and elective powers and their power to influence

foreign affairs. The heads of state endorsing NEPAD have recognised

the importance of good governance for African development. It is

now also up to parliamentarians to follow up on the African and international

commitments and monitor their implementation.

4. The objective of this report is to analyse what role parliamentarians

play in advancing the NEPAD agenda and meeting the 2015 target for

poverty reduction. It provides background on NEPAD and the commitments

of Monterrey and Paris. On this basis, it illustrates the existing

monitoring mechanisms and where parliamentarians can play a role

both in Africa and in Europe.

5. The Assembly has, with its

Resolutions 1449 (2005) on the environment and the Millennium Development Goals

and 1450 (2005) on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund

and the realisation of the Millennium Development Goals, already

contributed to mobilising parliamentarians and governments for development

issues by underlining the importance of the MDGs. As part of the

yearly report on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) and the world economy to the enlarged Parliamentary

Assembly, the committee also reviews the OECD’s work in increasing

the effectiveness of its members’ development co-operation efforts.

6. The rapporteur would like to thank not only his colleagues

who made helpful suggestions but also the experts who contributed

to the hearings organised by the Committee on Economic Affairs and

Development in the course of the preparation of this report: Mr Eugene

Owusu, Senior Advisor, Strategic Africa Partnerships, UNDP Brussels

Office; Dr Jeff Balch, Director for Research and Evaluation, AWEPA;

Mr David Gakunzi, then Head of the Dialogue Unit, North-South Centre

of the Council of Europe; Mr Denis Huber, Executive Director of

the North-South Centre; Professor Ben Turok, MP, member of the South

African Parliament and Chairman of the NEPAD Contact Group of African

Parliamentarians; Dr Eckhard Deutscher, Chairman of the OECD Development

Assistance Committee (DAC); Ms Doris C. Ross, Assistant Director

of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) offices in Europe; Mr Jean-Christophe

Bas, Development Policy Dialogue Manager for the External Affairs

Vice-Presidency of the World Bank; and Professor Uwe Holtz, member

of the Society for International Development, former Chairman of

the Parliamentary Assembly Committee on Economic Affairs and Development

and former Chairman of the German Bundestag Committee on Economic

Co-operation and Development. Naturally, the rapporteur bears sole

responsibility for his report.

2. The New Partnership for Africa’s Development

2.1. Background

and objectives

7. NEPAD represents a “vision

and strategic framework for Africa’s renewal”. Drafted by five African

heads of state,

it

was endorsed by the Organisation of African Unity – now the African

Union (AU) – at its summit in 2001. Its main significance lies in

the fact that it is an African led strategy for development and

that it entails strong political commitments by the participating

heads of state. It therefore represents a benchmark against which

leaders can be held accountable and a framework into which the international

community’s efforts can be placed. It is so far a programme of the

African Union with its own secretariat in South Africa. There are, however,

strong advocates for formally integrating NEPAD into African Union

structures, which would substantially increase the bureaucratic

burden on the programme (

Jeune Afrique 2007

).

8. The strategy centres around four primary objectives: the eradication

of poverty, b. placing African countries

on a path of sustainable growth and development, c. the integration of Africa in

the global economy and the end to its marginalisation in the process

of globalisation,and the acceleration of women’s empowerment. In

order to achieve these objectives, sectoral priorities have been

defined. These are notably infrastructure (such as communication

infrastructure, energy, transportation, water and sanitation) and

human resource development, but they also include agriculture, the

environment, culture, and science and technology.

9. NEPAD’s founders have acknowledged the fact that good and

responsible governance is key to overcoming the hurdles to Africa’s

development. Unaccountable governments, waste of resources and corruption

have for a long time hampered sustainable economic growth and equitable

social development. In the NEPAD Framework Document, political leaders

take joint responsibility to “promote and protect democracy and

human rights in their respective countries by developing clear standards

of accountability, transparency and participatory governance at

the national and subnational levels”.

10. The most important mechanism to improve governance in participating

countries is the APRM, created by the African Union two years after

the adoption of the NEPAD strategic document. The voluntary compliance and

mutual learning mechanism is open to all 53 African Union states.

Historically, African leaders have not been keen to discuss governance

issues on a regional or international level. With the adoption of

the APRM and despite continuous setbacks in individual countries,

there are strong hopes that a genuine discussion on andcommitment

to good governance will take hold. The concept of peer review and

learning assumes that a noncoercive, gradual convergence of policy

and practice in participating countries is more effective for building well-governed

systems than coercive attempts or straightforward conditionality.

11. The APRM reflects NEPAD’s diagnosis that good governance is

key to creating a positive investment climate as a prerequisite

for sustained economic growth. The country assessment therefore

also includes various dimensions of governance: democratic and political

governance including efficient public sector governance and the

fight against corruption; economic governance including the implementation

of transparent, predictable, and sound macroeconomic policies as

well as sound and transparent public finance systems; corporate

governance including the creation of a favourable business environment,

sound regulations, and codes of conduct for ethical corporate governance.

As a further element, the APRM also looks at the socio-economic

development of a country and its capacity to shape its own development

process and mechanisms for implementing development policies.

12. By now, 28 countries have signed up to the APRM and have thereby

in principle declared their readiness to undergo a review of their

governance systems and practices. It is interesting to note that

six of the participating countries are rated as “not free” and 13

as only “partly free” by Freedom House. This partly dispels fears

that only the best performers would stand up to the test. In the

first round of assessment, a country committee prepares its own

review through a consultative process. After a review visit by a

team from a peer country, the country self-assessment report and

plan of action are finalised. These form the basis for review by the

APRM forum of heads of state or government. The resulting documents

provide civil society and parliaments with powerful tools to hold

governments accountable. At the same time, throughout the process,

it is expected that governments have an incentive to improve their

governance to avoid naming and shaming. It is to be hoped that more

countries will take part in this constructive evaluation process,

which can contribute to a positive development climate, and that

the findings will be acted upon.

13. In moving from a framework document to a strategic action

plan, NEPAD sets out actions at the African and also on the international

level. Subscribing to the Millennium Development Goals, the founders

of NEPAD estimate that a total of US$64 billion would be needed

annually to reduce the number of people living in poverty by half

by the year 2015. It is expected that the bulk of this will have

to be levied from external sources and notably Official Development

Assistance (ODA). Private capital flows are described as a “longer-term

concern.” Furthermore, NEPAD calls on developed countries to open

their markets for African products.

14. With its emphasis on African ownership in connection with

a call for increased financial assistance, NEPAD is in line with

the broader context of international development policy making of

recent years. A struggle for more (and more effectively used) money

for development cooperation has been at the core of international

conferences, which followed the UN Millennium Summit in 2000. Country

ownership and alignment of aid withcountry plans and strategies

is one of the central elements of delivering better money.

NEPAD

in the context of international conferences: relationship with the

UN Millennium Development Goals, the Monterrey Consensus 2002, and

the Paris Declaration 2005

15. At the end of the Cold War, high hopes were placed on new

paradigms of development co-operation independent from the great

powers’ interests and open to genuine partnership. However, ten

years later, policy makers had to admit that progress was too little

and too slow to contribute significantly to the eradication of poverty

and to mitigate global imbalances. The main focus of concern was

Africa, where human development indicators showed no signs of improvement.

At the UN Millennium Summit in 2000, world leaders thus adopted the

Millennium Development Goals as clear and quantifiable targets for

improving the living standards of people in developing countries.

The overall goal of reducing poverty by half by 2015 is catalysed

and complemented by targets in the areas of health, education, gender

equality, and the environment.

16. At the Monterrey Conference “Finance for Development” in 2002,

over 50 heads of state, finance ministers and foreign ministers

reached an agreement on a new partnership between developing and developed

countries to achieve the MDGs. They recognised that the main responsibility

for progress lies with the governments of developing countries themselves

and hinges notably on their ability and willingness to put in place

appropriate policy and institutional frameworks. At the same time,

they acknowledged that countries would not be able to achieve these

goals without significant assistance from the international community.

On a quantitative level, participants called on “developed countries

that have not yet done so to make concrete efforts towards the target

of 0.7% of gross national product (GNP) as Official Development

Assistance to developing countries and between 0.15% and 0.20% of

GNP of developed countries to least developed countries”. On a qualitative

level, the agreement calls on donors to make greater efforts to

harmonise their procedures, to untie aid, and to adopt frameworks

that are owned and put forward by developing countries.

17. The quality of aid was the focus of the March 2005 Paris High

Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness. Improving the quality of aid entails

a greater focus on results of development co-operation and the reduction

of transaction costs. Core principles of the Paris Declaration on

Aid Effectiveness are therefore ownership, alignment, harmonisation,

managing for results, and mutual accountability. It was agreed that

developing countries would exercise effective leadership over their

development process and that donor countries would align their support

with national development policies. Through improved co-ordination

and harmonisation of procedures aid would be used more efficiently.

Furthermore, donor and developing countries pledged that they would

be mutually accountable for development results.

18. The commitment to increase Official Development Assistance

was prominently reiterated by G8 countries at their Gleneagles Summit

in July 2005. Of the additional annual US$50 billion of Official Development

Assistance, half was committed to Africa. The continent has been

a particular focus of the G8 since the presentation of the NEPAD

document and the adoption of the Africa Action Plan at the 2002 Kananaskis

Summit. In Evian in 2003, the expanded G8-NEPAD partnership created

the Africa Partnership Forum to monitor commitments and generate

international support for NEPAD.

2.2. Progress

so far

19. The political dynamic surrounding

Africa’s development has, at least partly, been underpinned by a surge

in economic growth. Since 1997, growth in real GDP in Sub-Saharan

Africa has been at 3% or above. In 2005 and 2006, it was even above

5%. It was estimated at 6.6% in 2007 and projected at 6.5% in 2008

(IMF, Regional Economic Outlook, Sub-Saharan

Africa, April 2008). Although this expansion is attributable

to rising production in oil exporting countries, it is interesting

that oil importing countries have also experienced high growth rates,

due to strong domestic investment fuelled by progress on macro-economic

stability and reforms in most countries. The region also benefited

from strong demand for its commodities, increased capital inflows, and

debt relief. Despite this positive picture, observers remain critical

about the impact of this economic recovery which remains vulnerable

to the risks of a global economic slow-down, rising inflation, weak

domestic policy implementation and political instability. Although

the share of people living in extreme poverty fell by 4.7 percentage

points from 1999 to 2004, the number of poor still remains constant

at nearly 300 million due to high population growth (World Bank, Global Monitoring Report 2007. It

is widely expected that the income MDG of reducing poverty by half

by 2015 will not be met for Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, the continent

is also lagging behind in most other indicators, although evaluating

progress in many countries is difficult because statistics are weak.

Chart 1: Better performance

Growth in sub-Saharan Africa is strongest in decades

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook, and IMF,

African Department database

20. Building on the premise of

a new partnership approach, a number of monitoring mechanisms have

been proposed and implemented for the actions foreseen in the NEPAD

framework and the commitments of the international community. At

the 2003 G8 summit, African and G8 leaders established the Africa

Partnership Forum as a monitoring mechanism for NEPAD. Its mission

is to “catalyse action and to co-ordinate support behind African

priorities and NEPAD”. Based at the OECD, a support unit co-ordinates

the forum composed of personal representatives of NEPAD subscribers’

heads of states, the AU, heads of regional economic communities,

the head of the African Development Bank, heads of state of development

partners, the president of the European Commission, and heads of

selected international organisations.

21. The latest published progress reports (presented in 2006 in

St Petersburg) are those on infrastructure, the fight against HIV/Aids,

and agriculture. They conclude that “little or no progress has been

made” in the field of agriculture. For HIV/Aids and infrastructure

they state that steps have been taken in the right direction but that

much more still needs to be done. Particular efforts have to be

made in accelerating implementation of projects and programmes in

infrastructure and in addressing the needs of vulnerable groups

in the fight against HIV/Aids.

22. As NEPAD’s core element, the APRM is the focus of particular

attention in evaluating NEPAD’s progress. Only three countries have

so far concluded the process and published their results (Ghana,

Kenya and Rwanda). Two have completed the process but not yet published

results (Algeria and South Africa) and another nine have started

the assessment. The quality of the process has reportedly been high

in Ghana with widespread civil society and parliamentary involvement.

In Rwanda, Kenya and South Africa, it is reported to have been dominated

by the executive. It has also been noted that parliamentary involvement

was very low both in the assessment process and theresulting follow-up

of the country action plans. Moreover, there is a growing feeling

among the lead actors, including the United Nations Economic Commission

for Africa (ECA) and some participating countries, that the mechanism

may atrophy if it is not injected with the resources to implement

the plans of action emanating from the process. Moreover, concern

has been expressed about lack of political will to correct weaknesses

that have been identified in the process or even to identify them

properly in the first place (Manby, 2008).

23. The ultimate success of the APRM will be determined by how

well it walks the thin line between high standards on the one hand

and broad adherence by African countries on the other. High and

rigid standards might jeopardise the idea of gradual improvement

by preventing countries from signing up and concluding the process.

Lowering standards puts the credibility of the mechanism with the

international community and civil society organisations at stake.

This is important in so far as there is an implicit expectation

that well-performing countries can expect an increase in aid flows.

The main points of criticism are that the APRM is being implemented

too slowly and lacks teeth to force real change in poorly governed

countries.

24. From the perspective of the international community, the picture

in 2006 showed that donor countries were on track to meet the ambitious

commitments of Monterrey and Gleneagles. Official Development Assistance

had increased since 2004 by US$25 billion to US$104.4 billion, which

represented 0.3% of OECD Development Assistance Committee members’

GNI. However, the lion’s share of this increase (US$18 billion) could

be attributed to debt relief, that is, outstanding debt from governments

or under government guarantees that is written off by the creditor

country. The years 2005 and 2006 saw exceptional debt relief to

Nigeria and Iraq, which boosted ODA figures.

Figure 1: Components of DAC donors’

net ODA

Most of the recent increase in aid is due to debt relief

Source: OECD/DAC.

25. The influence of unusual debt

relief also needs to be taken into account when evaluating the latest OECD

DAC figures on ODA in 2006. According to the OECD DAC, ODA from

DAC members fell by 4.5% mainly due to a decline in debt relief.

On a positive note, ODA did not really fall as much, because the abovementioned

debt relief distorts the picture. On a negative note, however, excluding

debt relief, ODA still fell by 0.8% in 2006 compared with 2005.

The combined ODA of the 15 DAC-EU members rose slightly by 2.9% in

real terms (taking account of inflation and exchange rate movements),

from US$55.8 billion in 2005 to US$59 billion in 2006. This represented

0.43% of their combined GNI, surpassing the EU collective ODA/GNI

target of 0.39%. In order to meet their international commitments

until 2010, OECD countries will still have to considerably step

up funding for development projects, programmes and technical co-operation.

The DAC estimates that “the present rate of increase in core development

programmes will have to more than double over the next four years

to fulfil the pledges.”

26. With regard to their commitment to doubling aid to Africa

by 2010, DAC donors are also facing great challenges. Since 2004,

aid for development projects, programmes, and technical co-operation

to Africa has barely increased. On the surface, ODA numbers look

better due to the increase in debt relief and humanitarian aid.

Between 2004 and 2006 total ODA to Africa rose from US$29.3 billion

to US$43.4 billion

However,

in order to meet the 2010 goals, aid for projects and programmes

has to increase substantially. One factor to be reckoned with is

that the target will be all the more difficult to meet in periods

of strong economic growth since ODA targets are defined as shares

of GDP but budget decisions in parliaments are debated with absolute numbers.

This has already spurred the establishment of new financing mechanisms

(such as the air ticket levy) and it might well be that debates

over adjusting the definition of ODA within the OECD DAC will intensify.

27. As already stated, the international community has not only

promised to deliver more aid but also to deliver better aid. The

first round of monitoring of the targets for effective aid delivery

of the Paris Declaration was completed in 2006. The report showed

a mixed picture and considerable need for progress. According to the

OECD Secretary-General and OECD DAC Chairman, all donor agencies

“have made major efforts to implement the Paris Declaration within

their organisations.” Donors also seem to increasingly understand

that countries need to determine their own priorities, pace, and

sequencing of reforms. However, implementation is slow. Countries

complain about the slow pace of change in donor practices, especially

when it comes to donor-driven technical co-operation and the only

reluctantly abandoned practice of tying aid. Donors also have a

long way to go in cooperating in their missions and programme implementation.

Countries still have to bear a high number of individual donor visits,

which are time consuming and entail high transaction costs (in 2005, the

34 developing countries covered by the survey received 10 507 donor

missions, more than one for each working day). The next round of

monitoring is taking place in the first quarter of 2008 for discussion

at the High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness to be held in Accra,

Ghana, from 2 to 4 September 2008.

3. Mobilising

parliaments for African development

28. In development policy thinking,

the 1990s can be considered the decade which focused on the role

of the state in advancing the development of poor countries (see

“World Development Report 1997: The State in a Changing World”).

The notion of an effective state, however, has been equated with

an effective executive (ODI, 2007) and largely focused on civil

society for checks and balances. Only slowly, and with increasingly critical

thinking about the role of NGOs, have parliaments in developing

countries received attention as actors in development. They are

formal institutions and draw direct legitimacy from the population

through a growing number of free electoral processes. As such, they

have come to be seen as actors that should play a greater role in

poverty reduction.

29. The new partnership approach to development as described above

entails a growing role also for parliaments. It is already a step

forward that international agreements on development include clear

targets and indicators for monitoring them. Institutional monitoring

mechanisms for governmental commitments are, however, until now

solely composed of representatives from the executive (such as the

OECD DAC or the Africa Partnership Forum). Parliamentarians in both

Africa and Europe can take a more active role in monitoring and

evaluating progress and implementation of these commitments and

policies. This was also one of the recommendations of the Cape Town

Declaration of European and African parliamentarians of May 2006.

30. Due to the nature of political systems, the difference in

capacities of parliaments, and the various kinds of actions needed,

the role of parliaments in Africa and in Europe will be examined

separately.

3.1. The

role of African parliaments – building capacity and widening parliamentary

space

31. The 1990s saw the return of

multiparty politics throughout Africa. African parliaments are gradually emerging

from their roles as rubber-stamps of the executive and are beginning

actively to take part in policy making and in the monitoring of

their executives. Although the degree of influence and independence

of parliaments varies greatly among countries, they are “arguably

more powerful today than at any time since independence” (Barkan

et al., 2004). The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa’s

“African Governance Report 2005” found that about a third of African

parliaments are “largely free from subordination to external agencies

in all major areas of legislation.”

32. Although this represents considerable progress, the optimistic

picture should not belittle the huge challenges that still lie ahead

for African parliaments. Over half of them cannot act independently

from other governmental agencies (UNECA, 2005). Constitutional reforms

have theoretically increased the power of parliaments but political

realities do not always match these prescriptions. Strong executives

still shape African politics and the constitutional role of parliaments

remains limited in many countries. Few parliaments have independent

funding (through dedicated budget lines) which renders them dependent

on ad hoc funding by the executive.

33. In addition to these external constraints, there are a number

of internal constraints and limits of parliamentary capacity. African

parliamentarians are amongst the most poorly remunerated throughout

the world. This prevents the best and the brightest from entering

parliament or makes parliamentarians rely on alternative sources

of income. This not only takes away time from parliamentary work,

it also facilitates corruption and favouritism (UNECA, 2005).

34. Furthermore, many parliaments lack basic resources such as

offices, libraries, electronic equipment or parliamentary staff.

The parliament of Malawi, for example, meets only eight to ten weeks

a year due to financial constraints. The Malian parliament employs

merely five parliamentary assistants for 11 committees (Barkan et

al., 2004; UNECA, 2005). Lack of access to information and means

of communication with constituencies prevents informed parliamentary

discussion and effective oversight of the executive.

35. In assessing the role of parliamentarians in African development

these constraints and challenges have to be taken into account.

Calls for increasing their role have to consider the available human

and financial resources and how quickly they can be built up. Parliamentary

involvement can only be built gradually and according to the institutional

setting of a country. Dialogue attempts should be careful not to

exclude those which are more difficult to access. At the same time,

the lack of parliamentary capacity should not be a justification

for sidelining them in development policy making. Capacity building

and parliamentary involvement should go hand in hand.

36. Parliament’s roles in the various development policy tools

and strategies such as NEPAD and the attainment of the MDG is fundamentally

linked to the proper functions of any parliament. Among a variety

of roles for parliaments and parliamentarians, three stand out as

particularly important: legislation, oversight, and representation.

Irrespective of the specific shape of political systems or the political

culture of a country, these are important channels for parliaments

and parliamentarians to shape policies and their country’s future.

37. In their capacity as legislators, parliamentarians discuss,

evaluate, and pass laws that constitute a country’s legal framework

and that have an important effect on economic and social development.

The Poverty Reduction Strategies initiated by the World Bank are

a vivid example for increasing parliamentary involvement in development

policy making at a country level. Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers

(PRSPs) are designed as a country’s plan for macroeconomic, structural,

and social policies for three-year economic structural adjustment

programmes to foster growth and reduce poverty. In the past, parliaments

have largely been sidelined in the PRSP process. The implementation

of PRSPs has, however, frequently met resistance from national parliaments

when it comes to introducing or changing the required laws. As a

result, there is a growing consensus that parliaments must be systematically

involved in the drafting of PRSPs and in subsequent implementation

and monitoring.

38. The monitoring of policies and a strong relationship of accountability

between the different branches of government are at the core of

the NEPAD process. Through parliamentary oversight, governments

and the donor community can be held to account if goals are not

met as measured by the various indicators attached to development

programmes. The APRM provides a powerful tool for parliamentarians

to put their governments’ feet to the fire. Calling on governments

to sign up to the APRM and to undergo a review of the country’s

governance system will be harder to ignore the more countries sign

up. Parliaments must also be involved more systematically in overseeing

the implementation of the country action plan that results from

the APRM process.

39. The budgeting process is any parliament’s most powerful way

to ensure oversight and accountability of the executive. Fiscal

transparency rules and public expenditure management systems (including

gender and development budgeting) are at the core of development

programmes that are delivered as budget support and other forms

of programme-based approaches. Many bilateral and multilateral agencies

now deliver a significant share (between 30% and 50% for the European

Commission, the United Kingdom, the World Bank and others) as direct

contributions to a country’s general budget. These contributions

are mostly linked to the introduction of budgetary transparency

rules and public sector reform programmes. Parliaments can take advantage

of this new space and transparency and critically analyse and debate

budgets. Each ODA allocation should include a percentage of the

grant which is set aside for parliamentary oversight by the relevant committee

in the recipient country.

40. Where aid flows are not directly linked to a country’s budget,

the lack of transparency and predictability of aid flows makes it

difficult for parliaments to keep track and hold governments accountable.

Donors should therefore provide timely, transparent and comprehensive

information on aid flows in order to enable partners to present

comprehensive budget reports to both their parliaments and their

citizens. Donors should allow recipient country parliaments to co-decide

on ODA priorities and targets, allow parliament to test objectives against

NEPAD goals, and provide resources for inter-parliamentary dialogue

on ODA effectiveness between donor and recipient country MPs.

41. The function of representation describes the role of parliamentarians

as a link between the executive and the people. It is about collecting,

aggregating and expressing the concerns and preferences of citizens. Moreover,

parliamentarians are also a voice through which they can explain

to the citizens they represent, and inform them, about public policy

choices and trade-offs. With respect to NEPAD and poverty reduction,

this is an especially vital function. Citizens need to be engaged

in the process so that it can establish a solid grassroots base.

In order for parliamentarians to act as a voice to the people, they

need to have sufficient access to information themselves.

3.2. In

Europe (for example, parliamentary committees, and so on)

42. As an African initiative first

and foremost, watching over the implementation of NEPAD is primarily

a task for African parliamentarians. The role of European parliaments

is to support their African counterparts in this endeavour. On the

one hand, this means to monitor their governments’ commitments to

development co-operation. On the other hand, parliaments can engage

in dialogue with their African counterparts in order to better inform

policy making and streamline policies with development issues.

43. Parliamentarians in donor countries are well placed to play

an effective oversight role over their governments’ development

policies and aid commitments. The mechanisms and intensity with

which development issues are followed in national parliaments varies

across European countries. Some countries have established parliamentary

committees on development policies. Others are mainly concerned

with development issues when it comes to budgetary discussions and

the allocation of development assistance.

44. The most immediate way for parliamentarians to get involved

is by scrutinising their governments’ performance on agreed indicators

for quantity and quality of aid. The OECD DAC’s reports on the quantity

of aid delivered by its members provide parliamentarians with a

basis for questioning governments if commitments were not honoured.

45. However, development co-operation is about more than delivering

aid and supporting development programmes in poor countries. A coherent

approach to development policy also includes scrutiny of other policy

arenas that have an impact on developing countries. Aid flows become

less significant if their effects are offset by distortionary policies

such as agricultural subsidies or trade restrictions against developing

countries’ products. Providing market access for African goods and

reducing domestic subsidies is generally considered as an important

step towards integrating African countries into global markets and

value chains. NEPAD addresses this in its “Market Access Initiative”.

Other areas with more or less direct impact on African countries are

agriculture, migration, employment, finance, environment, science

and technology, security and defence.

46. Very few countries have so far introduced formal mechanisms

for ensuring policy coherence for development. With its policy for

global development, Sweden is the first OECD country to formally

require that all policy areas have to contribute to global poverty

reduction and the realisation of the Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs). This policy is accompanied by extensive monitoring mechanisms

such as an annual report to parliament. The Netherlands has a unit

charged with ensuring policy coherence. It is based at the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs and provides reports to parliament and issues

coherence indices. Such reports would be an important tool for parliamentary

debate beyond the development committee.

47. The Center for Global Development highlights the importance

of coherence in its Commitment to Development Index. The Washington-based

think tank provides an alternative measure of donors’ performance.

In order to capture a more comprehensive picture of development

cooperation, it measures a country’s performance in the fields of

aid, trade, investment, migration, environment, security, and technology. For

example, the index penalises countries that give with one hand (through

aid or investment) but take away with the other (through trade barriers

or pollution). Among the best performers on this score are the Netherlands

and the Scandinavian countries.

48. Information is also a prerequisite for effective involvement

of European parliamentarians in NEPAD and African development. While

NEPAD attracted considerable attention at its inception and with

the endorsement of the G8, its evolution is rarely discussed. This

phenomenon not only applies to parliamentary discussions. Media

coverage of African issues in general mainly focuses on political

and humanitarian crises. Updates on or analyses of progress of NEPAD

activities or the APRM are rarely seen.

49. Parliamentarians engaged in development co-operation policies

will often find that they need to undertake considerable efforts

to explain development policies to their constituents. The practice

of tying aid represents a case in point. While development co-operation

has often been marketed as fostering market entry for domestic products,

governments have committed within the OECD to untie aid. Parliamentarians

need to be able to inform and give arguments to constituents and

business lobby groups as to why aid should be untied. According

to a Eurobarometer 2005 survey, 80% of citizens perceive development

narrowly as aid but nonetheless support development aid and their

government’s pledges. A Eurobarometer 2007 survey confirms this,

adding the perception that Sub-Saharan Africa is in greatest need

of European development assistance. Relating to constituencies and

building public support for comprehensive development policies would

also increase the weight of parliamentarians’ arguments vis-à- vis

the executives.

3.3. African-European

Parliamentary Co-operation (Association of European Parliamentarians for

Africa (AWEPA), Parliamentary Assembly Co-operation Agreement with

the Pan-African Parliament (PAP), etc.)

50. In addition to national parliaments,

regional parliaments, parliamentary networks and assemblies play an

increasingly high-profile role in fostering development co-operation

and dialogue. While they formally lack teeth to hold governments

accountable, their resolutions and recommendations are widely acknowledged

as important contributions to global policy making. They can provide

national parliamentarians with backing for views that would otherwise

go unnoticed or be hardly recognised in national parliaments.

51. Perhaps their single most important function is to provide

a platform for networking among parliamentarians to exchange views,

experiences and examples of best practice. For European parliamentarians,

they can be an important source to inform their own policy makers

on African issues and development. For African parliamentarians,

they are an opportunity to learn about the variety of political systems

and forms of organisation in order to see which could be models

for their own countries.

52. AWEPA addresses these goals. The core functions of the association

are strengthening parliamentary capacity through exchange and raising

awareness for development issues. This international non-governmental

organisation counts some 1 500 members from parliaments of EU member

states plus Norway and Switzerland and from the European Parliament.

Its roots lie in the campaign to end apartheid in South Africa.

Founded in 1984, the association through its members contributed

to the framing of sanction policies through laws, monitoring and

implementation. Its present work focuses on supporting parliaments

in Africa and keeping African issues high on the political agenda

in Europe.

53. The Pan-African Parliament, as an institution of the African

Union (AU), is initially designed as a forum for consultation on

the AU’s policies. Launched in 2004 to ensure that governments carry

out their developmental promises, it is envisaged that the parliament

will be granted more power in the future. In March 2005, the Pan-African

Parliament passed a resolution calling on national parliaments to

“urge their governments to accede to APRM as a demonstration of

their commitment to democracy and good governance in Africa”. Having

said that, the Pan-African Parliament includes some parliaments

(its second vice-president is from Libya) whose democratic credentials

are dubious. Nevertheless, as an organ of the African Union, it

is a natural forum for the monitoring of NEPAD’s progress. In this

context the rapporteur recalls the agreement concluded by the Parliamentary

Assembly with the Pan-African Parliament in 2005 and considers that

steps should be taken to implement it more actively, notably with

a view to strengthening the latter’s role as a parliamentary forum

for reviewing the activities of such institutions as the African

Development Bank. This could be modelled on the Assembly’s role

as a parliamentary forum for such international institutions as

the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and

the OECD.

54. Other interparliamentary institutions and networks involved

in mobilising parliaments in Europe and Africa, in strengthening

their capacity and involvement in development issues and in promoting

NEPAD include the Inter-Parliamentary Union, the European Parliament,

the Parliamentary Network on the World Bank (PNoWB), the African

Parliamentarians’ Forum on NEPAD, the NEPAD Contact Group of African Parliamentarians,

the African Parliamentarians’ Network Against Corruption (APNAC)

and, in the context of the preservation of Africa’s environment

and its capacity to produce its own food, the Parliamentary Network

on the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (PNoUNCCD).

4. The

role of the European Centre for Global Interdependence and Solidarity

(North-South Centre)

55. The European Centre for Global

Interdependence and Solidarity (North-South Centre) is the Council

of Europe’s prime mechanism for dialogue with developing countries.

As a part of the Council of Europe, it promotes the fundamental

values of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. Its focus

is on promoting dialogue between Europe and its southern neighbours

from the Mediterranean region and Africa.

56. The North-South Centre has been facilitating dialogue through

a series of Europe-Africa meetings. In preparation for the Europe-Africa

Summit in Lisbon in December 2007, the centre held a successful

Euro-African Youth Summit, to be followed up by a programme from

June 2008 to November 2009 hopefully with financing from its co-sponsor,

the European Commission, as well as an interparliamentary conference

as an opportunity for parliamentarians to provide input to the official

summit. At the Cape Town conference in May 2006, organised by the

North-South Centre, parliamentarians took a first step. Their Cape

Town Declaration calls for parliamentary monitoring of the EU-Africa

strategy and activities under the 10th European Development Fund

under the Cotonou Agreement.

57. With its expertise in promoting human rights protection and

advancing democratic governance, the North-South Centre is well

placed to focus on these areas in its exchanges with African parliamentarians.

It is furthermore an advantage that the Council of Europe includes

countries which have themselves recently experienced and completed

the transition to democracy. Sharing this experience with African

parliamentarians can be a useful way to engage in a constructive

dialogue on an equal basis.

58. The North-South Centre, as a partial agreement of the Council

of Europe, is in crisis as a result of the withdrawal of Italy and

France, two major contributors to the budget. It is vital that the

centre is placed again on a sound financial footing and that its

programme of activities correspond more closely to the needs and interests

of its stakeholders. The accession of Montenegro on 1 March 2008

is a hopeful sign that the process of restoration of confidence

has begun. In an increasingly wide network of parliamentary dialogues

and capacity-building programmes, it is especially important that

activities are well defined and targeted. Ad hoc and donor-driven

conferences are far too often limited to declarations and reports

posted on the Internet. While dialogue processes have per se no

measurable outcomes, some form of follow-up or implementation of activities

ensures the effectiveness of such efforts.

5. The

European Union-Africa Summit

59. The European Union-Africa Summit

held in Lisbon on 8 and 9 December 2007 adopted a joint strategy and

action plan to provide the means and instruments to implement the

new strategic partnership that is supposed to characterise the future

relationship between the two continents. Although still based on

European solidarity towards Africa in the struggle to overcome poverty

and fulfil the Millennium Development Goals, the partnership is

designed to go beyond the development framework and relations between

donor and recipient. The action plan comprises eight separate partnerships

for the period 2008-10 (when the next summit is planned): peace

and security; democratic governance and human rights; trade, regional

integration and infrastructure; Millennium Development Goals; energy;

climate change; migration, mobility and employment; and science,

information society and space. The objectives, expected outcomes

and activities are set out for each area and are to be implemented

through more frequent high level political contacts, including between the

Pan-African Parliament and the European Parliament and other institutions

of the African and the European Union, civil society, joint expert

groups, research institutes, and so on. It is to be hoped that national parliaments

will also be fully involved in promoting and overseeing the implementation

of the joint strategy and action plan.

60. At the Lisbon Summit, the EU signed the country strategy papers

of the 10th European Development Fund (EDF) with 31 countries of

Sub-Saharan Africa, providing a total of €8 billion over the period

2008-13. These co-operation programmes, worked out bilaterally with

each country, detail the priorities and results expected by 2013,

and these reflect the eight partnership areas of the EU-Africa Summit

action plan. One of the new features of the 10th EDF is that provision

is made (totalling €2.7 billion) for an “incentive tranche” to reinforce

a mutual commitment to good governance. Strategy papers with the

other Sub-Saharan countries are under way. Again, it is impor-tant

that parliaments play their part in ensuring the effective implementation

of these programmes.

61. In preparation for the Lisbon Summit, on 25 October 2007 the

European Parliament adopted a comprehensive resolution on the state

of play of EU-Africa relations.

Among

other things, the resolution stresses that national and continental

parliaments in both Africa and Europe have an important role to

play in improving governance and accountability as regards aid commitments

and better donor co-ordination with a view to taking greater account

of the so-called “aid orphans” (paragraph 36). It points out that

parliaments should exercise full scrutiny over programming and sees

ACP-EU Joint Parliamentary Assembly reviews of ACP Country Strategy

Papers as a first step (paragraph 47). It acknowledges the usefulness

of budget support, in particular for improving basic social services,

but underlines that it is not appropriate in the case of fragile states

or countries in conflict, and insists that it be accompanied by

the strengthening of the capacity of parliaments (paragraph 90).

It insists that national, regional and continent-wide parliaments

must be expressly considered as beneficiaries of aid (paragraph

100); and it states that parliamentary scrutiny and approval of development

assistance packages must be a requirement for the disbursement of

funds (paragraph 105).

6. A

look at some key issues

62. From the above analysis, it

is clear that parliamentary monitoring is important. In addition,

through questions and debate, parliaments also contribute to agenda

setting. Two issues in today’s development discourse should thus

be highlighted: the role of good governance for development and

the empowerment of women.

63. Good governance has become both a condition for development

assistance and a goal in itself. It is widely recognised that good

governance is a vital prerequisite for development. The increasing

number of indices and reports on governance reflects that there

is so far no perfect indicator or methodology for assessing governance.

For parliamentarians, the recently established Open Budget Index

might be of particular interest. Based on questionnaires completed

by local experts in 59 participating countries, the index assesses

the availability of key budget documents, the quantity of information

they provide, and the timeliness of their dissemination to citizens.

64. As a particular aspect of governance and one of special relevance

in most African countries, the fight against corruption has led

to the creation of a specialised network. The highly active African

Parliaments Network Against Corruption (APNAC) has chapters in participating

countries in close co-operation with Transparency International.

It provides parliamentarians with tools and information for combating

corruption. Most importantly, it provides a platform to exchange

experience of what works and what does not.

65. Gender equality and the empowerment of women according to

the UN’s definition – require improved access of women to rights

(equality under the law), to resources (equality of opportunity),

and to voice (political equality). Improving gender equality has

a positive effect for poverty reduction and growth directly through women’s

greater labour force participation, productivity, and earnings as

well as indirectly through the beneficial effects of women’s empowerment

on the well-being of children and families.

66. African parliaments are not doing much worse than European

parliaments when it comes to the representation of women in parliament.

According to statistics by the Inter-parliamentary Union, women

in OSCE member countries account for 19.8% of parliamentarians in

the single or lower house. In Sub-Saharan Africa, these are 16.8%

and thus more than in Asia or the Arab countries. These numbers

are, of course, not representative for the situation of women in

their respective societies.

67. An important element within the parliamentary process is the

scrutiny of the budget from a gender equality perspective (see Parliamentary

Assembly

Recommendation

1739 (2006) on gender budgeting). According to the

Global Monitoring Report 2007, more

than 60 countries have, over the last decade, undertaken analyses

of public budgets to assess differential incidence and effect on

men and women, as well as to measure men’s and women’s economic

contributions. Although it has to be acknowledged that not all parliaments

have the capacity for this kind of analysis, public scrutiny of

the budget from a gender equality perspective is a useful tool for

parliamentarians. It is important for both mainstreaming gender

in government policies and empowering citizens to influence policy-making

and hold governments accountable for public financial management.

7. Conclusions

and recommendations

68. This report has attempted to

analyse the role of parliamentarians – in both Europe and Africa

– in advancing the agenda of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development

(NEPAD) and in meeting the 2015 target for poverty reduction and

other Millennium Development Goals. It has provided background on

NEPAD and the commitments undertaken at Monterrey in 2002 with a

view to financing the achievement of the MDGs and in Paris in 2005

aimed at increasing the effectiveness of aid. It has taken stock

of progress made so far in Africa’s development and described existing

monitoring mechanisms and the ways in which parliamentarians can

play a role both in Africa and in Europe.

69. In general, there is a need to step up bilateral parliament-to-parliament

dialogue and co-operation on the subject of Official Development

Assistance, whether at the national or continental levels. In this

context the Parliamentary Assembly and the Pan-African Parliament

should take steps to implement their agreement more actively, and

the joint statement adopted by the European and Pan-African Parliaments

in advance of the Lisbon EU-Africa Summit in December 2007 is to

be welcomed.

70. Parliaments should involve themselves more closely in development

issues. National parliaments might consider establishing development

co-operation committees where they do not exist. Parliamentarians

must be duly mobilised and informed, and in this context the work

of such non-governmental bodies as AWEPA and the PNoWB is essential.

71. The APRM is an important African Union initiative that aims

to improve governance in participating countries, on the assumption

that good governance is key to creating a positive investment climate

as a prerequisite for sustained economic growth. African leadership

over such initiatives should be maintained but Council of Europe

member states and their parliaments should follow developments critically

and sustain their support.

72. In Africa, there is a need for a greater role and involvement

of parliaments in policy making and monitoring (Millennium Development

Goals, Africa Partnership Forum, African Peer Review Mechanism,

New Partnership for Africa’s Development, Poverty Reduction Strategy

Papers), as well as a need for capacity building and institutional

strengthening. Parliamentarians should play their full constitutional

role in relation to the executive.

73. In Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly should endorse and prioritise

the concept of parliamentary involvement in and scrutiny of Official

Development Assistance. There should be more effective monitoring

of commitments both in quantity and quality. There should be greater

policy coherence. Parliamentarians should be mobilised to take African

and other development issues into account and to explain the importance

of these issues to their constituents.

74. The experience of international co-operation has shown that

sharing of experience and good practice improves the quality of

policies. Among other institutions, the North-South Centre of the

Council of Europe has a wide range of experience on which to base

new work focusing on global development education and on good governance

based on human rights, democracy and rule of law. It is vital that

the centre regain the full confidence of the Council of Europe member

states by pursuing programmes that correspond more closely to the

needs and interests of its present and potential stakeholders, with

the full support of the Parliamentary Assembly.

8. Selected

sources

Africa Partnership Forum, Progress reports, 7th meeting of

the Africa Partnership Forum, Moscow, Russian Federation, 26 and

27 October 2006.

Africa Partnership Forum, Revised terms of reference for Africa

Partnership Forum, 5 October 2005.

Jeune Afrique, “Autodestruction

programmé”, 25 March 2007.

Barkan et al., “Emerging Legislatures: Institutions of Horizontal

Accountability”, in: Levy, Brian and Sahr Kpundeh, Building State Capacity in Africa,

World Bank Institute, Washington, DC, 2004, pp. 211-256.

Bayley, Hugh and Turok, Ben, “Holding Governments to Account

on Commitments to Development. A Best Practice Toolkit for Parliamentarians

in Africa, Europe and the West”, October 2005.

Bio-Tchané, Abdoulaye and Vibe Christensen, Benedicte, “Right

Time for Africa”, Finance and Development, December

2006, Volume 43, No. 4.

Hebaum, Harald, “Making the African Peer Review Mechanism

(APRM) Work. A rough road ahead for NEPAD’s key component”. SWP

working paper FG6, 2005/05, Berlin, December 2005.Hubli, Scott K.

and Mandaville, Alicia P. “Parliaments and the PRSP”, World Bank

Institute Working Papers: Series on Contemporary Issues in Parliamentary

Development, 2004.

IMF, “World Economic Outlooks”, 2007, 2008.

IMF, Regional Economic Outlooks, Sub-Saharan Africa, 2007,

2008.

Nijzink, Lia, Mozaffar, Shaheen and Azevedo, Elisabete, “Parliaments

and the enhancement of democracy on the African continent: An analysis

of institutional capacity and public perceptions”, in: The Journal of Legislative Studies,

12 March 2006, pp. 311-335.

Manby, Bronwen, Was the APRM process

in Kenya a waste of time? Open Society Institute, April

2008.

NATO Parliamentary Assembly, 2006 Annual Session, “G8 commitments

to developing countries”, rapporteur: Hugh Bayley.

The New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), Framework Document,

www.nepad.org.

OECD, Statement by Mr Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary General,

and Mr Richard Manning, Chairman, OECD Development Assistance Committee

(DAC), Development Committee meeting, Washington, 15 April 2007.

OECD, “Development Cooperation Reports”, 2006, 2007.

Overseas Development Institute (ODI), “Parliamentary strengthening

in developing countries”, Report to the United Kingdom Department

for International Development, February 2007.

Radelet, Steve, “Aid Effectiveness and the Millennium Development

Goals”, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, February

2004.

Stultz, Newell M., “African States Experiment with Peer- Reviewing.

The APRM, 2002 to 2007”, in: Brown Journal

of World Affairs, 13:2 (summer/autumn 2007).

Terlinden, Ulf, “Good Governance in Africa – a Parliamentarians’

Forum on Realistic Policies in North and South”, summary of discussions,

conference convened by the Development Policy Forum of InWEnt, Capacity Building

International, Germany.

UK Department for International Development, Policy Division,

“Helping Parliaments and Legislative Assemblies to Work for the

Poor. A Guide to the Reform of Key Functions and Responsibilities”,

July 2004, www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/helping-parliaments.pdf.

UK House of Commons International Development Committee, “The

Commission for Africa and Policy Coherence for Development: First

do no harm”, First Report of Session 2004-05.

United Nations, “The Millennium Development Goals Report 2007”,

New York, 2007.

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, “African Governance

Report” 2005.

_______________

World Bank, “Global Monitoring Reports” 2007, 2008.

Reporting committee: Committee on Economic Affairs and Development.

Reference to committee: Doc. 10905 and Reference No. 3236 of 26 June 2006.

Draft resolution adopted by the committee on 2 June 2008.

Members of the committee: Mr Márton Braun (Chairperson),

Mr Robert Walter (Vice-Chairperson) (alternate: Mrs Claire Curtis-Thomas), Mrs Doris Barnett (Vice-Chairperson), Mrs Antigoni

Papadopoulos (Vice-Chairperson), MM. Ruhi Açikgöz,

Ulrich Adam, Mrs Veronika Bellmann, Mr Radu Mircea Berceanu, Ms Guđfinna

Bjarnadóttir, MM. Vidar Bjørnstad,

Jaime Blanco Garcia (alternate: Mrs Elvira Cortajarena), Luuk

Blom, Pedrag Bošković, Patrick Breen,

Gianpiero Carlo Cantoni (alternate: Mr Dario Rivolta),

Erol Aslan Cebeci, Ivané

Chkhartishvili, Valeriu Cosarciuc, Ignacio Cosidó Gutiérrez, Joan

Albert Farré Santuré, Relu Fenechiu, Carles Gasóliba i Böhm, Zahari

Georgiev, Francis Grignon, Mrs Arlette Grosskost, Mrs Azra Hadžiahmetović,

MM. Norbert Haupert, Stanislaw

Huskowski (alternate: Mrs Danuta Jazłowiecka),

Ivan Nikolaev Ivanov, Jan Jambon (alternate: Mr Luc van den Brande), Miloš Jevtić,

Ms Nataša Jovanović, MM. Antti Kaikkonen, Serhiy Klyuev, Albrecht Konečný, Bronislaw Korfanty, Anatoliy Korobeynikov,

Ertuğrul Kumcuoğlu, Bob Laxton,

Harald Leibrecht, Ms Anna Lilliehöök,

MM. Arthur Loepfe, Denis

MacShane, Yevhen Marmazov,

Jean-Pierre Masseret, Ruzhdi Matoshi, Miloš Melčák,

José Mendes Bota, Mircea Mereută, Attila Mesterházy, Mrs Olga

Nachtmannova, Mrs Hermine Naghdalyan, Mr Gebhard Negele, Mrs Miroslawa Nykiel, Mr Mark Oaten, Mrs Ganira

Pashayeva, Mrs Marija PejčinovicBurić,

MM. Manfred Pinzger, Viktor

Pleskachevskiy (alternate: Mr Nikolay Tulaev),

Claudio Podeschi, Jakob Presečnik,

Jeffrey Pullicino Orlando, Maximilian Reimann,

Roland Ries, Mrs Maria de Belém Roseira (alternate: Mr Maximiano Martins), Mrs Gitte Seeberg, Mr Samad

Seyidov, Mrs Sabina Siniscalchi (alternate: Mr Giorgio Mele), MM. Giannicola Sinisi, Leonid

Slutsky, Serhiy Sobolev, Mrs Aldona Staponkienė, MM. Christophe

Steiner, Vjaceslavs Stepanenko, Vyacheslav Timshenko (alternate:

Mr Yury Isaev), Mrs Arenca

Trashani, Ms Ester Tuiksoo, MM. Miltiadis Varvitsiotis, Oldřich Vojíř, Konstantinos Vrettos, Harm

Evert Waalkens, Paul Wille, Mrs Gisela Wurm, Mrs Maryam Yazdanfar.

NB: The names of the members who took part in the meet ing

are printed in bold.

The draft resolution will be discussed at a later sitting.