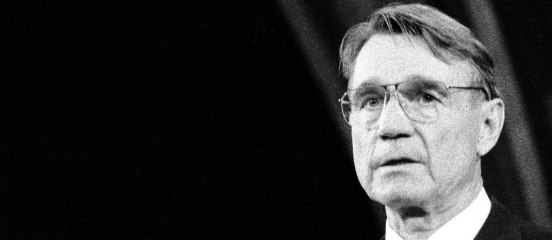

Mauno

Koivisto

President of Finland

Speech made to the Assembly

Wednesday, 9 May 1990

First, I thank you, Mr President, for your invitation to address this esteemed Assembly. It is an honour and a great pleasure for me to share some views on the future of our continent with you.

This Assembly was the first body in Europe to bring together parliamentarians to work for the noble Ideals enshrined in our Statute: parliamentary democracy, individual freedom, political liberties and the rule of law.

These ideals are deeply rooted in Finnish society. Having been an integral part of Sweden for more than 600 years, and thereafter a non-integrated part of imperial Russia, Finland has cherished the Nordic traditions of liberty and human rights throughout her history. A parliamentary reform in 1906 gave all Finns universal suffrage, irrespective of sex and social status; we were only the second country in the world, after New Zealand, to do this. Our present Constitution, adopted in 1919, is one of the oldest still in force in Europe.

I wish to reaffirm Finland’s commitment to the principles laid down in the Statute.

The first convention adopted by the Council of Europe was the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. That convention and the institutions created through it – the European Commission and the European Court of Human Rights – constitute the most complete international system for protecting human rights.

The Minister for Foreign Affairs of Finland will tomorrow deposit instruments of ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights and its protocols, and make declarations on the right of individual citizens to lodge a complaint and on Finland’s recognition of the jurisdiction of the Court.

Having participated in much of the work of the Council of Europe for nearly three decades and having enjoyed full membership for one year, Finland is committed to promoting and developing the role of the Council in our changing continent.

The decision to span a bridge between the Assembly and parliamentarians in Central and East European countries has been an important step in efforts to overcome the division of Europe. We strongly support it.

I am convinced that, through expanding membership and also through special arrangements appropriate for non-member states, the Council will play a growing role in the evolution of European societies and in promoting co-operation in our continent.

Europe is changing. This change is so swift and fundamental that hardly anyone could have predicted such a chain of events only a year ago. All those who regard themselves as experts on international politics feel incompetent.

Yet even this is not unprecedented. It is possible to predict or at least extrapolate stable development, whilst upheavals are always impossible to foresee.

As a statesman once said:

“Not a single principle in the management of our foreign affairs, accepted by all statesmen for guidance up to six months ago, any longer exists. There is not a diplomatic tradition which has not been swept away.”

Those words were spoken by the British Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, nearly 120 years ago, when the German empire had just been born and the politics of Europe were reshuffled.

Change liberates, but it also brings uncertainty and tension.

We are living in a time when old wrongs are being put right and accusations of new ones are laying the groundwork for future tensions.

When traditional confrontations recede, new ones – or, indeed, old latent ones – may arise. There are signs of that in today’s Europe.

Yet I am confident that the positive elements will prevail in the future. I believe that Europe is maturing to a security that will endure.

Europe is fulfilling the commitment made in Helsinki in 1975. The Final Act laid the groundwork for today’s changes in the political, military, economic and social relations of our continent.

No single factor has contributed to the recent rapid developments more than the change in the Soviet Union and in its international politics. But it is the new spirit of understanding between East and West which has made it possible for us to leave the cold war.

A year ago, this Assembly had the opportunity to hear President Gorbachev’s views on the reconstruction of Europe on a basis of common values and a balance of interests. Politics based on blocs and the traditional balance of forces must be left behind, was his message.

It is in the nature of this process that it will never be completed. A Europe that is one and peaceful, co-operating and progressing to its full potential, can emerge only through consistent work and mutual learning.

Setbacks will lie ahead as well, but they can be overcome if we have a proper sense of priorities.

We have to strengthen common structures in Europe. To continue the process, we must rely on the principles and experiences that have made our gains to date possible. But, to meet the challenges ahead, we shall have to develop our methods of co-operation further.

Even during the unnatural division of Europe, the authors of the Helsinki principles respected European diversity. They safeguarded national identity and self-determination, then and for the future.

As we upheld the ideals of human rights, we also freed the creative power of individual aspirations. We gave individuals the crucial position that they can and must have in the spiritual and material well-being of Europe.

Last month, at the CSCE Conference in Bonn, the participating states recognised the relationship between political pluralism and a market economy. The orderly conduct of political change in Eastern and Central Europe is encouraging.

Multi-party democracy, the rule of law and respect for human dignity foster economic development and facilitate reform. Those things, in turn, create a foundation for just social progress and stable peaceful relations in Europe as a whole.

Political pluralism and the market-place have become the focus of a heavy burden of expectations.

With advancing democracy and improved cooperation, the whole of Europe will be better equipped to meet the challenges of economic restructuring that lie ahead.

As the Bonn document declares, Europe is undergoing a profound and rapid change. In Western Europe, the challenge is economic integration. In Central and Eastern Europe, the goal is, first and foremost, economic recovery.

Europe cannot expect to reap the reward for overcoming political and ideological division if the gap of economic inequality remains or becomes even wider.

The Bonn Conference showed that European countries see their chance to expand and recognise their responsibility for expanding economic co-operation in an effective and yet balanced way. Markets can perform only in an economic environment of openness and reciprocity.

The transition to a market economy will be facilitated through the gradual creation of a common economic area in the whole of Europe. Co-ordinated support for sustainable economic reform will be a vital component in the coming together of European economies.

Co-operation in the development and introduction of environmentally sound technology is a prime example of what a new Europe, united in its purpose, could achieve. Only through cooperation can the damage be remedied and the environment preserved for future generations.

The arms race has become an economic burden for Europe. The new political opportunity and hard economic necessities speak for a profound reassessment of investment in the military factor and of its role in our security relations.

The historic results in sight in disarmament negotiations will give us a chance to break the endless cycle of arms expansion and modernisation.

Europe is on the threshold of freeing itself from the over-arming that has kept it captive for so many years and decades.

Individually, European countries are drawing their conclusions from the strain that armament puts on their national economies. This is especially true in countries whose economies have been under such excessive strain that they must now make a clear choice between armament and economic reform and recovery.

Just as vital is the fact that the military reality is being changed through disarmament. An emerging new strategic landscape will diminish the danger of military instability and conflict.

The negotiators in Vienna will have a chance to be true to their mandate and abolish the threat of surprise attack and large-scale offensive in the area where military confrontation was the symbol and basis for such fears in a divided Europe.

But what really makes us believe that deep cuts in armaments will give us more security is that they will be associated with effective verification, confidence-building measures and openness. The CSCE military negotiations in Vienna have an important task in this respect.

The more that openness is an integral component of military matters, the more credible disarmament measures and new security arrangements will be.

Judgments need no longer be made on the basis of mistrust or uncertainty. States can also reassure their neighbours and other countries of the peacefulness and sincerity of their policies and intentions.

Europe will then enjoy co-operative security.

Within the military alliances, a search for future roles and new functions seems to be taking place. Such functions may be found in the field of arms control and verification. We welcome this.

We are living in a period of transition which may last for a long time.

Historic steps are in sight, although not completed yet. Growing stability – even if it is the general trend – is not necessarily comprehensive or uninterrupted.

As East-West confrontation recedes, the major military powers continue to bear the greatest responsibility for security relations in Europe.

Regional sources of instability and conflict may assume greater significance for the whole of Europe. Relations between neighbouring states are likely to affect the maintenance of security and stability more than in the past.

Joint security arrangements function if neighbours and rivals are responsible and willing to solve their problems. A common security institution cannot solve our problems for us.

We greet with great satisfaction efforts towards regional co-operation in Central and Eastern Europe, which aim at going beyond old barriers and former practices and grasping both the opportunities and responsibilities that exist for co-operation and resolving conflicts.

One of Finland’s main policy principles is that of maintaining good relations with our neighbours and contributing to security and stability in northern Europe and the Baltic region. That is a vital environment for our national security.

We are following with great concern and sympathy the efforts of the Baltic peoples to find their way to independence, to which the Soviet Constitution also entitles them. Our own experience tells us that, with a great power as a neighbour, one has to reach negotiated solutions that will stand the test of time.

I speak as a representative of a country for which the greater powers projected the same fate as that of the Baltic nations. But we went along another road. This road led first through great difficulties and sacrifices, but later to a stable relationship with our neighbouring great power. The Soviet Union has become a good neighbour.

History cannot be undone, but the new chances that today’s Europe offers for all countries and peoples should be fully utilised.

The foundation of security is evolving together with, and as a result of, European political and economic change. In this way, learning from experience, a new and stable security order can take shape.

When we speak today of a new European security system, it needs to be seen in the light of a comprehensive development.

As Europe changes, more and more security functions will be entrusted to joint arrangements, procedures and institutions. In the long run, such a common system may become vital for national as well as international security.

The CSCE has a central role in the management of the ongoing change. There is a growing consensus that it will also provide the essential framework for future common security arrangements and co-operative regimes.

Finland has long spoken out in favour of strengthening the CSCE follow-up in a measured way.

We concur with the idea of holding periodic meetings of the Foreign Ministers of the CSCE-participating states. This is one of the issues to be considered at the summit meeting of the CSCE countries planned for later this year.

As a neutral country, Finland has been active in the CSCE process from the beginning. We are proud that the process carries the name of our capital, where the first summit took place.

As the CSCE process enters a new phase, we look forward to further opportunities and responsibilities.

The capability of the CSCE to respond to new and growing tasks should be strengthened. Finland is ready to offer her contribution and her services to this process.

As the host country, we look forward to the Helsinki follow-up meeting in 1992 with a sense of great responsibility and, of course, we shall be very pleased to see the summer meeting of the Council of Europe in Helsinki next year. We expect the meeting to find new tasks for the CSCE process and to make decisions on such new principles, institutions and working methods as will be deemed necessary by the participating states.

Helsinki 1992 will give Europe new guidelines to continue the journey begun at Helsinki 1975.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you, Mr President. We have listened to your statement with great interest and you can be sure that we are eager to have a dialogue with Finland about the role of the Council of Europe and the CSCE process. I cannot think of a better way of doing that than holding our summer session in Helsinki next year. We are very grateful that you have offered us the chance of visiting Helsinki.

You have been kind enough to agree to answer oral questions. I propose asking you to answer each question in turn. I shall then request the member concerned to ask a brief supplementary question, if he or she so wishes. I remind members that, according to the guidelines that have been approved by the Standing Committee, all oral and supplementary questions will be limited to thirty seconds. Yesterday, questions from the Assembly averaged twenty-one and a half seconds each, to be precise. That was extremely good. I hope that we can do the same today so that as many members as possible will have the chance to ask questions.

So far, nine questions have been proposed. First, I call Mr Alptemoçin, from Turkey, to ask a question about the relationship between the Council of Europe and the CSCE process.

Mr ALPTEMOÇIN (Turkey)

Thank you, Mr President. I should also like to thank his Excellency, the President of the Republic of Finland, for kindly agreeing to answer our questions. As you said, Mr President, my question is about the relationship between the Council and the CSCE process. Bearing in mind the similarity of the aims of these two structures in relation to human rights, culture and education, how do you think that co-operation between the structures can be developed? Do you think that the Council of Europe will act as the parliamentary wing of the CSCE?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

I understand that there is mutual interest in this because, on the one side, the Council of Europe wants to develop its activities and, on the other side, many tasks and goals need to be pursued in Europe. I believe that the Council of Europe is perfectly capable of fulfilling many of our future needs for co-operation. I understand that a means of achieving closer co-operation between the Council of Europe and the CSCE process – as yet, it is not an organisation – will be found and I believe that the parliamentary component of that cooperation could well be supplied by the Council of Europe.

THE PRESIDENT

Does Mr Alptemoçin want to ask a supplementary question?... No, well in that case, I thank President Koivisto for his positive statement and now call Mrs Harms to ask her question about co-operation between the Nordic countries and the rest of Europe.

Mrs HARMS (Denmark)

Thank you, Mr President. What does President Koivisto think of the idea of holding a co-ordinating meeting for the Prime Ministers of the Nordic Council before any important meetings in Europe, before the meetings of the Committee of Ministers, for example, here at the Council of Europe or before meetings of the EEC, of which the Nordic countries are not members, and before EFTA meetings?

In my opinion, such meetings would inspire us and improve the co-ordination of our ideas. They would give us a better chance of achieving the results for which we are aiming. Our arguments would carry greater weight if all five countries could stand behind each other.

I emphasise that we in the Nordic countries have a long tradition of co-operating with each other. It must be possible to use that experience, not only for our own benefit, but for that of the future of Europe. After all, not only do the Nordic countries need Europe, but Europe needs the Nordic countries.

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

The Nordic countries form a group that works well together, especially on social policy. The countries have a similar structure, and four are similar in size. There is therefore a need for co-operation, which has proved fruitful in the past.

Indeed, our Nordic Council holds fruitful discussions. The Nordic Prime Ministers meet three times a year and our Foreign Ministers also meet regularly. There is therefore a huge amount of contact at every level. Security policy is the exception, which is understandable, as three of the Nordic countries are members of NATO while two are neutral.

At present, four of the Nordic countries are members of EFTA and one is a member of the EEC. There are therefore many opportunities for co-operation and discussion and for finding mutually profitable ways of proceeding. I very much agree with the idea behind the question, and with continuing ongoing co-operation.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you, President Koivisto. As Mrs Harms does not wish to ask a supplementary question, I now call Mr Gudnason to ask his question about the effect of the increased importance of the Council of Europe in terms of regional co-operation.

Mr GUDNASON (Iceland)

Thank you, Mr President. First, I thank his Excellency, the President of Finland, for his excellent speech. My question is along the same lines as the previous one. In your speech, President Koivisto, you mentioned the profound and rapid changes that are taking place in Europe. Inevitably, they will change the scope and nature of the work of the Council of Europe and dramatically increase its importance. What effect do you think that that will have on regional co-operation in Europe, such as the co-operation between Nordic countries in the Nordic Council?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

Nordic co-operation is unique in Europe because of the activity and the discussions of the Nordic Council. It is not easy to imagine which other groups of countries could develop such close ties with each other and be so open to each other’s involvement in the domestic policies of our individual countries. There is no alternative to co-operation based on several other principles. I understand that there is co-operation between the different parliamentary groups and other interest groups of the Council of Europe. Our co-operation in the North could be an example to other countries when they see how fruitful and important our co-operation has been. Perhaps the Council of Europe could lend a hand in making our cooperation better known.

Mr GUDNASON

In your opinion, President Koivisto, should the Council of Europe make an effort to work more closely at a parliamentary level with regional organisations, such as the Nordic Council?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

I am not so well aware of your problems, Mr Gudnason, to be able to give a hand, but I am willing to put in a good word for Nordic co-operation. It has been extremely fruitful.

Mr ELMQUIST (Denmark)

I noted with interest what you said about your experience of having a big neighbour to the east. You also gave some advice to the Baltic states. Would you elaborate somewhat and advise members of the Council of Europe on how we can promote – if we have an opportunity to do so – negotiations between Moscow and the Baltic states?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

I have no special advice of my own, but I associate myself with the advice that was given some two weeks ago by President Mitterrand and Chancellor Kohl – that some kind of intermediary solution should be found so that negotiations can start on the new status of the Baltic republics. The Constitution of the Soviet Union makes it impossible for the republies to go their own way. There is a special law about procedures. The problem is that the Baltic countries, especially Lithuania, already regard themselves as independent and maintain that Soviet legislation does not apply.

The problem is that Lithuania asked to be recognised as an independent country at the beginning of these discussions and, although Moscow is prepared for talks that might lead to independence, it is not prepared to start with it. It is difficult for others to give more precise advice. When a big power and a small power are on a collision course, it is usually extremely difficult to criticise the small one.

Mr ELMQUIST

When it comes to aid, help or support – not only moral or political but in terms of energy or humanitarian aid – what is your advice to members of the Council of Europe? Should we give the Baltic states what they want when they ask for it or not?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

It is hardly possible to develop a general rule, but I suppose that we would all be very pleased if a way could be found to start real negotiations so that outsiders knew the proper way to behave.

Mr SPEED (United Kingdom)

As Finland fought for her independence fifty years ago, are you in a position to play a role, perhaps as an intermediary, in this very difficult situation between the Baltic states and the Soviet Union?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

As I said in my address, we have been in a position similar to that of the Baltic states. We have a great interest in and a lot of understanding of the situation; we are trying to follow what is going on there, but we do not have very close ties. We do not have any knowledge about the problems or the possibilities of solving them, and I doubt whether there are any other outsiders who are better equipped than us. It is difficult to know what it is advisable to do. Our general approach to world affairs has been to recognise that we are not wise enough to advise other countries on their business, and that is particularly true in this case.

Mr SOLÉ-TURA (Spain)

I thank the President for his wide view of the European situation, but I should like to insist that he say a little more about the problem of the Baltic countries. Finland’s position and relationships in a Europe that has been divided into antagonistic blocs have been specific and special. What is Finland’s role in the new political scenario in Europe? How can it be defined and how can it help implement real, not hypothetical, independence for the Baltic countries?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

It has proved very difficult to foresee events and developments in Europe during the past few months. The situation has changed quite unexpectedly, so to be able to speculate about the future, one should know much more than anyone knows. The number of actors is fairly limited and it should be possible at present to know their ideas and what they might expect from us. We have had a lot of contact with the Baltic countries, especially Estonia, with which we have special linguistic ties and a lot of social and other contacts. If an overall framework were defined between Moscow and the Baltic states, we would welcome that development with deep gratitude.

Mr SOLÉ-TURA

Do you think that Finland’s international relationships can be useful as a reference point for peaceful solutions to the present problems between the Baltic countries and the central Government of the Soviet Union?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

We have had a lot of problems in the past and the Soviet Union has had a lot of problems vis-à-vis my country, but we were able to find solutions. We adopted the ideas that were originally developed by Machiavelli in the Middle Ages, namely that it is advisable for a small country to find friends close by and enemies far away. One must respect a neighbour’s interests, including his security interests. It is important for the future of the Baltic states to make them understand that they can have a somewhat similar attitude towards their neighbour as we have had.

Mr ROKOFYLLOS (Greece) (translation)

Like several of my colleagues, including Mr Elmquist, I prepared a question about the Baltic states and their recent attempts to regain their independence. I would like to know how these attempts are viewed in the light of Finland’s own experience.

However, I shall not pursue this matter any further since other colleagues, of all political leanings, have already expressed their concern and sympathy for what the Baltic states are trying to do.

I should simply like to express my satisfaction with President Koivisto’s replies, which bear witness to his long political experience and impeccable wisdom.

Mr MORRIS (United Kingdom)

Mr President, you referred to the importance of the environment and your country is noted as a world leader in forestry matters. There is great anxiety in the world about the depletion and care of the tropical rain forests. Is it Finland’s policy to give particular help to the Third World and to advise on renewable forests?

Mr Koivisto, President of Finland

orests play an important role for Finland. We have few natural resources other than forests, so we have to give them special care. That is why we have a great deal of expertise and interest in helping others to understand and tend their forests. We are disturbed to see trees cut down and forests disappear. That has a great impact on the climate of the immediate area and causes erosion. On a large scale that might have a detrimental influence on the atmosphere of the whole globe.

We have been participating actively in the forestry programmes of many Third World countries. We are interested in international cooperation. I have been informed of a process of co-operation on a European basis in which Finland and France are playing an important role. The problem is close to our hearts.

THE PRESIDENT

I thank you, President Koivisto, on behalf of the Assembly for your speech and the way in which you have answered our questions. You are the first Head of State of Finland ever to address this Assembly. We are happy that you accepted our invitation to come here. We are happy, too, that Finland is a member of the Council of Europe. We hope for good future co-operation. I am sure that you will take an active part in the creation of the new Europe.

You were asked many questions about the Baltic states. People have asked for your advice and thoughts because they know that Finland has long had experience of relations with countries in that part of Europe. Please feel encouraged by all the interest that we have shown in your advice about this complicated question, which we all hope will be solved peacefully. Thank you once again for your contribution to the Assembly’s work today.