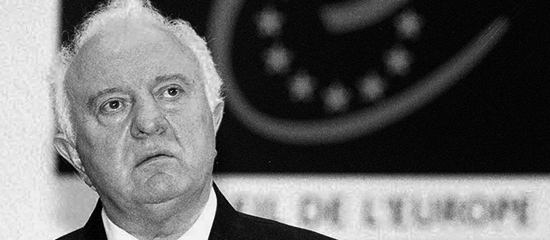

Edward

Shevardnadze

President of Georgia

Speech made to the Assembly

Tuesday, 27 April 1999

Mr Edward SHEVARDNADZE expressed his appreciation to all representatives of the Assembly and international delegations for their unanimous support for Georgia’s admission as a member of the Council of Europe. He thanked the Council of Europe for its commitment to democracy. In its fifty years the Council of Europe had made a remarkable contribution to the promotion of human values. The Council of Europe had been established to help Europe recover after the second world war but, with the cold war, the idea of a family of nations was doomed, with eastern Europe being isolated behind the Iron Curtain. Following the defeat of fascism, the end of the cold war was the second most significant recent European development and provided the opportunity for progress which was epitomised in the Council of Europe. The end of the cold war allowed a number of countries to take their rightful place in the family of Europe.

Georgia’s admission into the Council of Europe was an important prerequisite towards fulfilling its internal objectives. A society based on the rule of law and a market economy was wanted. Georgia had adopted a new constitution, including free elections and a constitutional court. It was important to note that the reforms had created an institutional respect for human rights. New civil codes had been adopted. Capital punishment had been abolished and an ombudsman established.

A tidal wave of change was sweeping through Georgia. Residents’ permits had been abolished and an environment had been created for an independent mass media. Legal standards had been harmonised with those in Council of Europe countries. Georgia had already acceded to a number of conventions and in 1999 a co-operation programme had been agreed between the Council of Europe and Georgia in the areas of the law and human rights. Co-operation in the fight against corruption was of crucial importance to Georgia. Georgia had created a special enforcement agency to fight corruption. Judicial reform was also under way to ensure that Georgia could gain its rightful place in the Council of Europe.

Georgia also had a role in developing relations and encouraging respect for human rights throughout the south Caucasus. He hoped that in the near future both Armenia and Azerbaijan would become full members of the Council of Europe. The objectives and values of the Council of Europe should be more comprehensively defined to enable countries to make the transition to democracy.

The ethnic cleansing in Kosovo had proved as disastrous as that as in Abkhazia. In Abkhazia over 300 000 people, mostly Georgian, had been driven out and thousands executed. Such widespread low-intensity local conflicts could trigger chain reactions, which could lead to a global confrontation, but international organisations still responded with rhetoric and watered-down resolutions. A new European order could not be created unless each country received equal attention and effort. Kosovo should not be regarded as an isolated event.

A peace process under the auspices of the United Nations would be the best way to solve the problem of Abkhazia. Georgia felt that Abkhazia should accept a place in a federation where the rights of all groups would be respected.

Mr Shevardnadze had just come to Strasbourg from Washington DC. Despite having left behind two world wars and the cold war, the future was not cloudless. Instincts for the recognition of threats had slackened and there were dangers present in making tepid responses in the face of threats to human rights. Nazi crimes, though of a different scale, had shown the tragic results which could ensue. Nor had Bolshevik crimes received a proper assessment. In the past, whole villages and nations had been “ethnically cleansed” in parts of eastern Europe. If peace talks were misused, for example by endless procrastination aimed at allowing crimes to become legitimised, they would be discredited. In general, diplomacy had to be backed by force.

Occupancy of the moral high ground should not be compromised by geopolitical considerations. A partnership was needed involving the European and Atlantic community. The Black Sea Co-operation, initiated by Turkey in 1992, provided a good example of an international organisation of growing weight. A potential belt of peace, the new Silk Route, was coming into being as a result of co-operation between the Black Sea and Caspian sea countries. Oil and gas transportation infrastructures were either complete or under construction. Georgia was at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, and was a partner of proven reliability. Reforms were continuing and, despite an acute energy crisis, industry and agriculture were being revitalised. Georgia had an affinity with European culture and had acceded to the European Cultural Convention in part with the aim of improving understanding of its cultural potential. This was one area in which Georgia was active in the Council of Europe.

He endorsed the creation of favourable conditions for human justice and supported the idea that the Council of Europe and the Committee of Wise Persons had proposed concerning self-renewal. The Council of Europe was vital for small states which, via the Assembly, could contribute to the world stage. He continued to be incurably optimistic about the creation of a new European order in the twenty-first century.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you very much indeed, President Shevardnadze, for your broad, humane and optimistic speech. As you know, members have expressed the wish to put questions to you. I have a list of seventeen questions. I therefore propose not to allow members to ask supplementary questions. In an effort to get everybody in, we have tried to group the questions according to subject, but the range of questions is so wide that that has not always been easy. The first two questions concern Georgia’s membership of the Council of Europe. To ask the first one I call Mrs Aytaman of Turkey, who is a member of the European Democratic Group, or the Conservative Group, if you like.

Mrs AYTAMAN (Turkey)

First, may I extend through you my heartfelt congratulations to the Georgian nation on Georgia’s well-deserved membership of the Council of Europe. The Turkish parliamentary delegation voted unanimously in favour of Georgia’s membership. Your country has excellent political relations with its neighbour, Turkey. Your close personal relationship with the Turkish President, Mr Demirel, and other high level Turkish officials contributes to the friendship of the two neighbouring nations. In Turkey you are a popular personality whose wisdom and friendship is greatly appreciated.

Now your country is a member of the Council of Europe, of which Turkey was a founder member. Some aspects of Turkish-Georgian relations fall within the priority areas of the Council, such as transfrontier cooperation and combating terrorism and organised crime. In view of that, how do you see the future of Turkish-Georgian relations, and to what extent can Georgia’s membership of the Council contribute to relations among the Caucasian countries?

THE PRESIDENT

I remind members that we are asking for questions of no longer than thirty seconds if possible, not speeches. Mr Shevardnadze, will you respond?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

confirmed that Georgia had an extremely good relationship with Turkey, both on a national basis and between the respective presidents. The big threat to their mutual arrangements was the burgeoning crime in the region, which had led to the development of a transit corridor for criminals and an increase of narcotics trafficking. He was, nevertheless, sure that the exemplary co-operation would continue.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. The next question is from Mr Behrendt of Germany, who is a member of the Socialist Group. It is on the same subject.

Mr BEHRENDT (Germany) (translation)

Mr President, allow me, on behalf of the German delegation, to congratulate Georgia on its accession to the Council of Europe. I am particularly pleased to do this because I am aware of the important role you played in the unification of Germany. Thank you very much.

I should like to ask a question on the situation of the minorities. As you know, the protection of minorities is an issue the Council of Europe considers very important. You said that you saw some progress towards resolving the conflict in Abkhazia. Do you consider that the Council's requirements regarding the protection of minorities have been met, and how do you assess the chances of satisfactorily resolving the other ethnic conflicts in this region – in Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that Georgia had unique experience over thousands of years in dealing satisfactorily with ethnic minorities.

Georgia had recently celebrated twenty-six centuries of Georgians and Jews living side by side. There were many other minorities in Georgia, including Armenians and Russians, all of whom had the same rights as Georgians. There were, however, problems. The state was still weak economically and could not do all that was required to help minorities because of financial limitations. Georgia’s position on the Silk Route could help it economically. Georgia had signed many conventions, the requirements of which would help its development.

THE PRESIDENT

I warn members that unless they adhere to the thirty second limit, we shall not have time for all the questions. We shall time questions on the clock so that members may see their progress.

The next question is from Mr Oliynyk, a member of the Socialist Group, who wants to ask about the territorial integrity of the sovereign states.

Mr OLIYNYK (Ukraine) (interpretation)

said he represented the European Left. He welcomed and complimented the President of Georgia. He asked whether, with the tragedy in Yugoslavia, the President had changed his view that separatism was a destructive force.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

returned the questioner’s compliments and said that aggressive separatism was an evil of our era.

THE PRESIDENT

The next question is from Mr Iwinski, who is a member of the Socialist Group, and who wants to ask about relations between Georgia and Russia.

Mr IWINSKI (Poland)

One of the results of the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 was the creation of several post-Soviet sovereign states, which has essentially changed the political map of Europe and, indeed, the world. For obvious reasons, Georgia’s relations with Russia remain crucial. How would you assess them, Mr President? Will you also comment on the role of the independent states and your country’s place in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that Georgia enjoyed a good relationship with Russia, although there were some difficulties. Some healing was required. He thought the CIS had a future only if it helped member states to guarantee their independence and help them economically. The last summit of the CIS had been held in that spirit.

THE PRESIDENT

The next question is from Mr Solonari, who is a member of the Socialist Group, and who wants to ask a question on Black Sea co-operation.

Mr SOLONARI (Moldova)

In your powerful speech, Mr President, you referred to the Black Sea Economic Co-operation Agreement, which you highly approve of and to which I fully subscribe. There is one more organisation which has signed an agreement; it comprises Georgia, Azerbaijan and Moldova. Will you share with us your assessment of how things are going within the framework of that agreement?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that the association of countries in the area had been formed under unusual circumstances. Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine had decided to expand their sphere of co-operation to include political topics. Uzbekhistan was a new member of the group which had particular interest in matters related to the Silk Route. The group, which had once concentrated on only one topic, now had a more comprehensive agenda.

THE PRESIDENT

The next question is from Mr Atkinson, the leader of the European Democratic Group the Conservative Group who wants to ask about Chechnya and Transcaucasia.

Mr ATKINSON (United Kingdom)

You have clearly acknowledged the new responsibilities that your country has entered into and of course it has new authority as the only Council of Europe member state in the southern Caucasus. Will you use that new authority to encourage Council of Europe standards in your neighbour, Chechnya, and to promote transfrontier co-operation and interparliamentary dialogue as the keys to long-term peace in the disputes on Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that a new organisation called the Movement for a Peaceful Caucasus had been set up to encourage co-operation between countries in the region. He wanted to foster friendship and good relations between Georgia and the Chechens and to promote progress.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. The next question is about minorities and displaced persons in the Caucasus. I call Mrs Durrieu, who is leader of the French delegation and a member of the Socialist Group.

Mrs DURRIEU (France) (translation)

Mr President, I would like to tell you, on behalf of the French delegation, how pleased we are that you are with us here today and thank you for expressing your ability to pardon, a word which we have hardly ever heard in this forum. I am also grateful to you for remaining resolutely optimistic.

Together with Armenia and Azerbaijan, Georgia is part of the geographical region of the Caucasus. Can this notion of region and regional co-operation help settle the problem of minorities? You have just answered that question, because Mr Atkinson, the previous speaker, asked a similar question.

I shall therefore ask another question, Mr President. If Russia participates in the settlement of the Kosovo problem, do you think that, logically, it should also immediately become involved in settling the issue of Abkhazia?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that it was his personal feeling that the achievement of a settlement would be accelerated if Russia became involved. Mr Chernomyrdin would be the best person to answer the question why Russia had not become involved.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. The next question is on transport co-operation. It is from Mr Dayanikli who is in the Socialist Group.

Mr DAYANIKLI (Turkey)

I express my excitement and happiness at seeing our Georgian neighbours as full members of the Council of Europe.

In a few days, the Assembly will discuss a report on pan-European transport policies. At this juncture, the new oil pipeline from Baku to Supsa is well worth mentioning as well as the planned Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan pipeline.

Given Georgia’s ever-increasing economic relations with Turkey and the close co-operation between the two friendly countries on transportation, what is your assessment of the rail and road links between the two countries for the Caucasus and central Asian states, and what measures is Georgia contemplating to improve its rail connections with Turkey? Thank you.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that Georgia was pursuing a number of plans, focusing particularly on railway links. There had been some problems securing funding, but a number of banks were showing interest. There were over one hundred joint ventures with Turkey in total.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. The next question is on the Silk Route. It is to be asked by Mr Muehlemann who is a Liberal from Switzerland.

Mr MUEHLEMANN (Switzerland) (translation)

Mr President, you referred a number of times to the Tracecca project to extend the Silk Route. Last year, your defence minister launched a courageous operation to put down a revolt directed against the completion of the oil pipeline.

How secure is the completion of this important project, and can western investors, who are important for economic progress in your country, count on legal certainty and support from your government?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

said that the recent attempt to destabilise the country had involved only a small group and was over in two hours. All authorities and institutions were now functioning as normal.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. There are now two questions on Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Mr Zierer.

Mr ZIERER (Germany) (translation)

Mr President, Georgia’s accession brings with it a number of rights, but also a number of duties. Like all other member states, Georgia is called upon to make every effort to meet the conditions of membership, especially as far as respect for human and minority rights is concerned.

I should like to ask what measures Georgia has taken so far in order to reduce its internal tensions on a lasting basis, for example in Ossetia and Abkhazia, and whether there are any concrete plans for future measures.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

replied that the conflict was in its final stages. In Abkhazia the situation was more complex and he thanked Germany for its assistance in this matter. With the help of the international community there were grounds for optimism.

Mrs ISOHOOKANA-ASUNMAA (Finland)

The Abkhazian conflict has remained unresolved for a long time. The situation appears to have deteriorated and reached deadlock. To what extent will it be possible in the foreseeable future to meet the Abkhazian demands of increased autonomy or some form of self-determination? How do you see the future of Ossetia? Does it seek autonomy as strongly as Abkhazia does?

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

replied that this was a central matter for Abkhazia and that Georgia was prepared to provide the highest possible autonomy. It would have its own constitution, parliament, and judiciary, but within a single Georgia. There were problems with the word autonomy, but these could be addressed in the spirit of negotiation and compromise. Now that people were returning to Ossetia, consideration could be given to their concerns. The OSCE and other European structures could help.

THE PRESIDENT

We are running out of time. We have two questions on the Meskhetian minority, which I shall call one after the other rather than separately. First, I call Mr Kelemen, who is a member of the Christian Democratic Group.

Mr KELEMEN (Hungary)

You have mentioned the painful situation of different groups of Georgian refugees. When I was the Rapporteur of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights I became a friend of Georgia. What developments have there been since your presidential decree on the Meskhetian people, who were expelled from Georgia under the regime of Stalin and who intend to go back to their homeland?

Mr KHARITONOV (Russian Federation) (interpretation)

congratulating Georgia on its accession to the Council of Europe, asked about the timescale to be adopted in respect of the implementation of minority rights.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

replied that he had already mentioned the repression of Stalin and the Bolsheviks, when thousands had died. The question of the Meskhetians, deported in the 1940s, was one of the most topical problems. They ought to be brought back over a period of time. Georgia had been working on an implementation plan covering both the number of people and their places of future settlement. Georgia was keen to see this injustice righted. He thanked the Russian Federation for supporting Georgia’s membership of the Council of Europe.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you. There are four questions left. I shall call them one after the other and I ask for them to be very brief. If we do that, perhaps we shall finish all the questions, which would be a minor triumph. I call Mr Cherribi, who is a Liberal.

Mr CHERRIBI (Netherlands) (translation)

The whole of Europe is talking about the problems we are likely to encounter when we enter the new millennium. We are all trying to reduce the risk. Is Georgia in a position to face up to this ordeal and combat the millennium bug, and how do you intend to deal with the problem posed by the state of the nuclear power stations inherited from the Soviet Empire’s period of stagnation? Are you receiving enough aid from the European Union?

We wish Georgia a good start after the weekend which opens the new millennium. Thank you.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

responding to the question from Mr Cherribi said that, while he was not a specialist in information technology, he was aware that the hydropower systems relied on computer technology.

THE PRESIDENT

You were very clear, Mr President. However, I would ask you not to answer until the end of the next three questions, which are on different subjects. I call Mr Kosakivsky.

Mr KOSAKIVSKY (Ukraine) (interpretation)

asked his question concerning local self-government in Georgia.

Mr GOULET (France) (translation)

Mr President, allow me to change the subject, although the previous ones are of the utmost importance.

How do you plan to capitalise on your country’s natural assets? I am referring in particular to the fact that Georgia has water resources which give it the potential to become a “reservoir” for the region and even for areas further afield. The country also offers possibilities for the development of tourism, given its well-preserved sites and rich historic, cultural and religious heritage. Owing to its favourable geographical location it offers a range of magnificent landscapes from the Caucasus mountains to the shores of the Black Sea.

In view of these assets, in my opinion Georgia cannot but be content with unfocused assistance from the Council of Europe.

What are the first concrete measures you would like to see introduced in the near future in order to establish a true partnership with Europe?

THE PRESIDENT

I call Mrs Squarcialupi to ask her question. As she is not present I invite Mr Shevardnadze to respond to the questions.

Mr Shevardnadze, President of Georgia (interpretation)

confirmed that municipal problems had been addressed. Local elections had been held. Within two years it would be possible to elect local administrations. The problem with Georgia’s plentiful natural assets was the lack of finance with which to develop them. However, foreign investment was now being attracted from a number of countries including Japan, the United States and the European Union. In due course, Georgia expected to attract large numbers of tourists. The Council of Europe would help Georgia and mutual co-operation would be further developed.

THE PRESIDENT

Thank you very much for your painstaking replies to the questions, Mr President. After that marathon, you deserve a good lunch. This being France, that is guaranteed.