1. Introduction

1. The right to protection of health is enshrined in

Article 11 of the revised European Social Charter, which is worth

recalling: “With a view to ensuring the effective exercise of the

right to protection of health, the Parties undertake, either directly

or in co-operation with public or private organisations, to take

appropriate measures designed

inter alia:

to remove as far as possible the causes of ill-health; to provide

advisory and educational facilities for the promotion of health

and the encouragement of individual responsibility in matters of

health; to prevent as far as possible epidemic, endemic and other

diseases, as well as accidents”.

2. Following

Recommendation

1626 (2003) of the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly

on the reform of health care systems in Europe: reconciling equity,

quality and efficiency, the Committee of Ministers declared in 2004

that “the Council of Europe will continue to play an important role

in assisting member states to incorporate the ethical, social and

human rights dimension in health policies and in reforms of their

health care systems. Continuing attention will be paid to access

for the vulnerable and in finding a new balance between curative,

preventive and promotive health care”.

3. In the Oslo Declaration on Health, Dignity and Human Rights,

the European Health Ministers meeting in Oslo on 12 and 13 June

2003 called for “a proper balance between preventive and curative

care, with a marked insistence on the development of healthy lifestyles.

For this purpose measures should be taken to develop individual

responsibility towards one’s own health, and ensure citizen participation

in the decision-making process concerning health care lifestyles”.

4. Budget constraints in the majority of Council of Europe member

countries weigh heavily on the public funding of health systems

as currently organised. The various budgetary contexts therefore

produce health policies based more on the treatment of disease and

on health care systems than on preventive policies.

5. The European population is undergoing demographic changes,

including population ageing, which will have serious consequences

for individuals, communities and states, alter disease patterns,

particularly as regards chronic and non-communicable diseases, and

affect the viability of health systems. Chronic conditions are projected

to be the leading cause of disability throughout the world by the

year 2020. If not successfully prevented and managed, they will

become the most expensive problems faced by our health care systems.

6. Because of growing pressure on public finances as a result

of demographic change, it is becoming vital to develop a fresh approach

that will enable every individual to enjoy the highest possible

standard of health attainable and ensure that everyone has equitable

access to it whilst maintaining budgetary balance.

7. If health policies in Europe are to be effective, therefore,

they need to incorporate an overall preventive approach so as to

be able to assimilate and address health as a state of complete

physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence

of disease or infirmity.

8. The rapporteur believes that investing in prevention offers

obvious economic and financial benefits. Investment in disease prevention

and health promotion can not only preserve and improve an individual’s health

and quality of life but also increase the productivity of society

and maintain a population’s work capacity. It can prevent early

death and early retirement resulting from disease, reduce business

production losses, maintain the independence of the elderly and

avoid or delay care needs.

9. At the same time, disease prevention and health promotion

enhance the population’s health competence and can thus lead to

a more highly differentiated demand for and use of health provision,

which can help to reduce the rising cost of health systems in the

long term.

10. However, inequalities in access to health education, information

and care still exist, with a well educated part of the population

who enjoy easy access to the resources allocated and disadvantaged

groups who experience greater difficulties. The real issue is therefore

how to secure access to the available resources for those most in

need.

11. An ever increasing percent of health care costs in all European

countries are attributable to chronic and preventable diseases the

kind that conventional medicine does very badly with. Our system

rewards and nurtures a therapeutic culture in which the goal is

primarily to fix what goes wrong. We have a “sickness culture” and

we need to get into a “health culture”, which must remain accessible

to the whole population.

12. This report will review existing preventive approaches to

health care and health promotion. These policies require a long-term

vision which is not completely the case yet in the Council of Europe

member states, despite existing recommendations made by several

international organisations. The rapporteur will also probe into

the costs of inaction, the advantages of prevention and the obstacles

to a genuine and comprehensive preventive health care policy. Finally

the report will discuss a number of policy pointers to take into

account when designing health promotion strategies, drawing from

the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the

conclusions of the Council of Europe European Committee of Social

Rights as well as recent public health research reports.

2. Who does

what at the international level

13. Disease prevention and health promotion have assumed

increased importance in international health policies. However,

national health policies and structures reflect deeply rooted values

and norms which differ between societies. Because of substantial

inter-country differences, it cannot be assumed that concepts are shared:

terms such as prevention, health promotion and public health are

used differently, which prevents direct comparison.

14. However, certain clear tendencies, as reflected in important

policy documents and in recommendations by European and international

organisations – in particular WHO, the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Commission and

the Council of Europe – can be discerned.

15. Policy approaches are increasingly aimed at more than changing

behaviour patterns and concern themselves with health inequalities

and health determinants, that is, with the underlying causes of

health and disease. This means that other political and social fields

must be incorporated in a forward-looking health policy.

16. Although comparisons can be made between health care systems,

there is as yet no comprehensive plan for the systematic listing

and analysis of the wide range of draft laws, policies and programmes

in the fields of disease prevention and health promotion.

Here follows a brief overview of activities

of the main international organisations dealing with preventive

health care policies and health promotion actions.

2.1. World Health Organization

(WHO)

17. For many years WHO has been stressing the need for

investment in health and has published documents which are among

the most influential in the fields of disease prevention and health

promotion, such as the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, the

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the Global strategy on

Diet, Physical Activity and Health and the 2008-2013 Action plan

for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable

diseases. As regards infectious diseases, WHO has created a global

surveillance system by setting up a “network of networks” which

combines the networks of medical laboratories and centres already

existing at the local, regional, national and international levels.

2.2. Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

18. The central theme of OECD work on health policy is

the measurement and improvement of the performance of health care

systems in member countries. Many countries possess a national framework

for measuring the performance of their health systems and have carried

out reforms. In its publication Health at a Glance 2007, the OECD

shows that health care quality, as measured by the provision of

suitable care or actual improvements in health, is making progress

in the OECD countries. However, the prevention and management of

chronic diseases pose an increasingly formidable challenge to health

policies.

2.3. European Union

(EU)

19. The EU’s health strategy focuses on health as a precondition

for economic progress, health inequalities between and within the

27 EU member states, health promotion in all policy sectors and

the mobilisation of all the parties involved. A programme of community

action in the field of public health for 2008-2013 is intended to

promote health in an ageing Europe, protect the public from threats

to health and encourage dynamic health systems and new technology.

Actions in the field of health and consumer protection are also

carried out and a European pact for mental health and well-being

helps to increase the population’s awareness of mental disorders.

2.4. Council of Europe

20. National representatives from 47 member states work

together with specialist experts to set out minimum guarantees to

safeguard human rights, the right to the protection of health and

indeed patients’ rights at the European level. Health protection

and promotion are two lines of action used to develop an ethical European

health policy. This is carried out by combining human rights, social

cohesion and health agendas, harmonising member states’ health policies

in terms of safety and quality, developing preventive medicine and health

education, and promoting patients’ rights, access to health care,

citizen participation and protection for vulnerable groups. Co-operation

activities carried out in co-operation with WHO and the European Commission,

such as the Schools for Health in Europe Network and the South-Eastern

Europe Health Network,aim

at bridging the principles and standards with real life practical

situations.

21. Preventive health care and health promotion policies certainly

benefit from transnational sharing of information and global co-operation.

However, while some overlap of activities from different organisations

is inevitable and different perspectives desirable, it would be

useful to ensure a more strategic interaction based on each organisation’s

area of specialisation. The existence of many interrelated mandates

can be confusing and redundant, especially when these must be implemented

within resource constraints that do not keep pace.

22. Efforts made by international and supranational organisations

as well as collaborative advocacy among NGOs have led to greater

recognition of the importance of health promotion policies, thus

showing a trend of policy convergence. However, there appears to

be convergence in officially stated policy but considerable divergence

in the willingness to actually implement that policy.

23. It is important to stress that health is essentially a state

responsibility and access to care remains a major concern that takes

precedence over the development of a prevention culture. While European

health systems are appreciated for their ability to make treatment

available to users at a reasonable cost, prevention policy, which

requires vision and the implementation of longer-term strategies,

does not seem to constitute a policy priority.

3. Costs of inaction

and advantages of prevention

24. At a time when budgetary pressures are having an

ever-increasing impact on how our health systems are organised,

it could be worthwhile to step up prevention policy in the hope

of making savings. One only has to take a look at the epidemiological

data to realise this.

25. Additional problems are raised by the ageing of the population.

By 2050 over a quarter of the population of the WHO European region

will be more than 65 years old. At least 35% of men over 60 suffer

from a number of chronic ailments; the number of co-morbidities

increases progressively with age and levels are higher in women.

The care of patients suffering from chronic diseases requires effective

health care services which promote health and are capable of managing

complex long-term diseases which require a patient-based approach.

26. Health indicators show a rise in chronic diseases and lifestyles

which are harmful to health. These are the symbolic diseases of

a global consumer society. Non-communicable diseases are currently

responsible for 86% of deaths and 77% of the burden of disease.

This group of conditions includes cardiovascular diseases, cancer,

mental health problems, diabetes mellitus, chronic respiratory diseases

and muscular/skeletal disorders. Cardiovascular diseases are the

chief cause of death inasmuch as they are responsible for half the deaths

in the region as a whole, with heart failure and stroke forming

the main cause of death in all countries.

27. According to WHO, seven risk factors account for nearly 60%

of the burden of disease in Europe: hypertension (12.8%), smoking

(12.3%), alcohol abuse (10.1%), raised cholesterol (8.7%), excessive

weight (7.8%), inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption (4.4%)

and lack of physical exercise (3.5%).

28. These common risk factors have economic, social, gender-linked,

political, behavioural and environmental determinants.

For

example, differences between socio-economic groups in regard to

mortality from cardiovascular diseases and risk factors giving rise

to the latter have been reported in numerous countries. Elimination

of the gap between lower and upper socio-economic groups offers

considerable scope for reducing mortality due to cardiovascular

disease and other non-communicable conditions.

29. By way of illustration, in addition to the health problems

linked to tobacco consumption, about 650 000 smoking-related deaths

occur every year in the EU. Nearly half the victims are between

35 and 69, well below average life expectancy. The direct and indirect

costs in Europe were estimated by WHO at between €97.7 and €130.3

billion in 2000, which represents between 1.04% and 1.39% of the

EU’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

30. People die from all chronic diseases at much lower ages in

central and eastern European countries than in Western Europe. For

example, in Hungary the cost of tobacco addiction amounted to 3.2%

of GDP in 1998, while in Finland and France the cost was estimated

at between 1.1% and 1.3% of GDP. In Sweden, the overall cost of

health care and smoking-related losses in productivity came to 26

billion Swedish kroner in 2001, which is comparable to the national

contribution to international aid (21 billion) or to the operation

of the legal system (23 billion).

31. In addition, the economic consequences of non-communicable

diseases exceed the direct cost of health services. It has been

estimated that in Sweden over 90% of total expenditure on muscular/skeletal

disorders are of an indirect nature (sick leave: 31.5%; early retirement:

59%). Premature death of the main breadwinner and of skilled workers

affects not only household income but also the national economy.

It has been estimated that the GDP of the Russian Federation was

reduced by 1% in 2005 as a result of non-communicable diseases.

32. WHO calls on countries to take measures and implement collective

action programmes aimed at the public at large, such as reduction

of the amount of salt in processed foods, reduction of the quantity

of fat in the diet, promotion of physical exercise and the consumption

of fruit and vegetables and smoking control. These actions are recognised

as the most effective ways of controlling cardiovascular diseases.

33. The first effect of prevention is to give the population as

a whole an improved quality of life by reducing the occurrence or

severity of disease and by allowing individuals to take control

over their health and well-being. Prevention also has substantial

financial effects in addition to these intangible benefits, as it

can lead to social security savings by reducing the length of time

workers are absent. A targeted prevention policy can also produce

savings in sickness insurance as such by avoiding or reducing the

cost of future treatment.

34. The competent authorities face a strong and steadily increasing

demand for an increase in the capacity of health systems to meet

the needs of consumers and patients, improve care quality and correct

disparities in health and access to care. The fact that an improvement

in general health represents an additional asset to economic growth

and therefore a further source of income is so well established

that one rarely sees it questioned. However, the rapporteur believes

that analysis of the role of power in influencing what policies

gain and lose remains currently neglected.

4. Obstacles to implementing

a genuine prevention policy

35. Data show that resources are allocated chiefly, and

at great expense, to the curative services and traditional medical

care, while primary prevention and health promotion are neglected.

On average, the OECD countries have earmarked scarcely more than

3% of their public health expenditure for a wide range of activities

such as vaccination programmes and public health campaigns against

alcohol and tobacco abuse. The great disparity largely reflects

the way prevention campaigns are organised nationally.

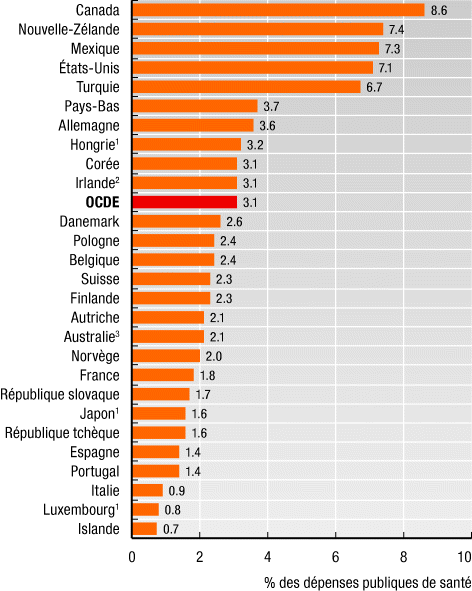

Proportion of public health expenditure allocated to

public health and prevention in OECD countries (2005)

% of public health expenditure

Source: OECD Health

2007

36. It seems, moreover, that compared with the budget

for curative medicine the public authorities’ efforts regarding

disease prevention and health promotions are minimal. Public expenditure

on disease prevention in the European area represented between 0.1%

and 0.5% of GDP. By way of comparison, the Czech Republic, Iceland,

Luxembourg and Poland devoted 0.1% of GDP in the same year. The

figures were 0.2% for France, Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal,

the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, 0.3% for Germany, 0.4%

for Finland, Belgium and the Netherlands and 0.5% for Hungary.

What are the reasons for this imbalance

between the funds allocated to prevention and those for the treatment

of disease?

37. A co-ordinated overall approach to prevention, a proper

continuum

based

on the participation of all parties concerned with health, education

and welfare and on the need for everyone to be aware of the importance

of health capital, encounters a number of obstacles, which are outlined

as follows:

37.1. A short-term vision:

expenditure on prevention presents a disadvantage for the competent

health authorities in that the effects of prevention efforts are

often only visible in the long term. Authorities embarking on a

large-scale prevention programme therefore run the risk of never

seeing the benefits of their policy (which are often reaped by their

successors);

37.2. Limited financial and human resources: most current health

care systems are based on responding to acute problems, urgent needs

of patients, and pressing concerns. Preventive health care is inherently

different from health care for acute problems, and in this regard,

current health care systems worldwide fall remarkably short. Prevention

budgets are always difficult to evaluate but are in any case modest.

The same applies to the staff allocated to prevention, whether they

are in school medicine, industrial medicine or public health medicine.

The training of staff not dedicated exclusively to prevention is,

furthermore, often inadequate;

37.3. The difficulty of enacting or enforcing binding rules:

this is sometimes due to the influence of powerful lobbies and economic

interests which have been able to prevent the passing of laws in

sectors such as food hygiene, agriculture, transport, industry,

tobacco and alcohol. Even when such laws exist they are often bypassed

and their application is sometimes left to the good will of the

parties involved;

37.4. The absence of genuine policy continuity and involvement

of the local authorities: prevention all too often consists of large-scale

national media campaigns without any real impact on action at the

local or field levels. Failure to assess the actions undertaken

has prevented certain innovative approaches from being pursued and

made a part of general practice;

37.5. The question of the role of the media: the information

they deliver to the general public sometimes interferes with the

perception of certain risks or of the true issues involved in disease

prevention. The close dependence between the issues on which public

opinion is focused, the policy decisions and budget allocations

often leads to a disproportion between the sums earmarked for the

reduction of certain risks and the seriousness of those risks.

38. Despite these obstacles, positive trends can be discerned,

particularly an increase in attention to strategies that concentrate

on health determinants and inequalities and focus on health gains.

Similarly, mental health is becoming more important, the introduction

of new partners is encouraging intersectoral collaboration and new

forms of organisation and financing, for example foundations, are

being tested in several countries.

39. Generally speaking, preventive actions remain all too often

based on a biomedical vision of health. Prevention can only be genuinely

effective in the health field if the living conditions available

to the population are such that it can avoid exposure to a number

of risks and is able to receive a preventive message.

5. A comprehensive

approach to preventive health care and health promotion policies:

some policy pointers

40. A country’s unique circumstances must be taken into

account when the time comes to decide on appropriate policies. National,

European and international studies and action plans on disease prevention indicate

a number of avenues to be explored or possibly useful approaches

for improving the performance of national health systems.

41. An increasing number of countries today are developing policies

and programmes that explicitly address the root causes of ill health,

health inequalities and the needs of those who are affected by poverty

and social disadvantage. This has led to a growing understanding

of the sensitivity of health to the social environment and to the

so-called social determinant of health.

Here follows a series of key actions,

policy pointers and challenges faced by policymakers:

41.1. Promoting better co-ordination

between the various policies and the so-called “health in all policies”

approach: an effective and innovative prevention policy must provide

a continuous cradle-to-grave strategy covering the preventive and

curative aspects and taking account particularly of the different

policies. Public policy can shape the social environment in ways

conducive to better health. Policies on social inclusion, education,

nutrition, agriculture, chemical production, industry, road traffic, transport,

alcohol or tobacco consumption or other fields which are not strictly

part of the health authorities’ responsibility have to be adapted

accordingly. The carrying out of health impact studies, for example

when a public policy is introduced, could assist such co-ordination

without endangering budgetary balance.

41.2. Actively co-operating with WHO and the global surveillance

system in order to halt the expansion of infectious diseases: globalisation

has brought about the rapid spread of new infectious disease, such as

SARS and HIV Aids and the re-emergence of others, such as tuberculosis

and malaria. HIV prevention, in particular, is consistently under-prioritised

in many national responses.

There

is increasing fear of global influenza pandemic and preparedness

is critical at all levels of health governance, in particular at

the international level.

41.3. Influencing risk prevention and reduction at the environmental

level (pollution, intensive use of antibiotics in livestock raising,

use of pesticides in agriculture, etc.): numerous measures aimed

at environmental hygiene are economical compared with more conventional

curative action in the health sector. To take the example of the

gradual elimination of leaded petrol, it is estimated that mental retardation

caused by exposure to lead in general is nearly 30 times higher

in regions where leaded petrol is still used than in those where

such use has ceased. The Assembly has recently examined this issue

with the Recommendation 1863 (2009) on environment and health: better

prevention of environment-related health hazards, which are referred

to for further information.

41.4. Incorporating prevention policies explicitly in poverty

reduction strategies and in relevant socio-economic policies: inequalities

in access to protection, risk exposure and access to care lead to

major inequalities in the emergence and outcome of disease. Disadvantages

tend to concentrate among the same people and their effects on health

accumulate during life. They can include having few family assets,

having a poorer education during adolescence, having insecure employment,

becoming stuck in a hazardous or dead-end job, living in poor housing,

trying to bring up a family in difficult circumstances and living

on an inadequate retirement pension. The longer people live in stressful

economic and social circumstances, the greater the physiological

wear and tear they suffer, and the less likely they are to enjoy

a healthy old age. Reducing educational failure, insecurity and

unemployment, improving housing standards, introducing minimum income

guarantees, minimum wages legislation and access to services can

help to redress the balance.

41.5. Supporting a good start in life for families and young

children: research shows that the foundations of adult health are

laid in early childhood and before birth. Slow growth and poor emotional support

raise the lifetime risk of poor physical health and reduce physical,

cognitive and emotional functioning in adulthood. Insecure emotional

attachment and poor stimulation can lead to reduced readiness for

school, low educational attainment, problem behaviour and the risk

of social marginalization in adulthood. Good health-related habits,

such as eating sensibly, exercising and not smoking, are associated

with parental and peer group examples, and with good education.

Slow or retarded physical growth in infancy is associated with reduced

cardiovascular, respiratory, pancreatic and kidney development and

function, which increase the risk of illness in adulthood. It is

critical to strengthen preventive health care before the first pregnancy

and for mothers and babies in pre- and postnatal, infant welfare

and school clinics, and through improvements in the educational

levels of parents and children.

41.6. Health education and health literacy must be a priority

of public health policy: people, children in particular, have a

right to learn about health and gain the health literacy skills

to lead a healthy lifestyle and navigate the consumer society. Health

literacy should form part of the curricula and explore the possibilities

offered by the new technologies, with a particular focus on smoking,

drugs, alcohol abuse, nutrition, mobility and safety, sport and

sex education. Participation of young people in shaping solutions to

their particular education needs is critical. Conditions at school

should also encourage the adoption of healthy behaviour through

pupils’ working, hygiene and dietary conditions. Periodical medical examinations

should be carried out throughout schooling. Immunisation programmes

should be widely accessible with high vaccination coverage rates.

Health care must be available to all children without discrimination,

including children of illegal and undocumented migrants.

41.7. Ensuring transparent decision making and accountability

in all food regulation matters, to provide affordable and nutritious

fresh food for all: a shortage of food and lack of variety cause

malnutrition and deficiency diseases. Excess intake, also a form

of malnutrition, contributes to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes,

cancer, degenerative eye diseases, obesity and dental caries. Food

poverty exists side by side with food plenty. There is confirmed

link between childhood obesity and deprivation. The important public

health issue is the availability and cost of healthy, nutritious

food. Sustainable agriculture and food production methods that conserve

natural resources and the environment should be further supported; developing

a stronger food culture for health, to foster people’s knowledge

of food and nutrition, especially aiming at children, remains critical.

41.8. Paying attention to the risks of stigmatisation: campaigns

on nutrition and healthy body weight may have unintended negative

consequences and should not stigmatise overweight people, who are likely

to deny their problem; they should also keep a watchful eye on people

at risks of developing body image and eating disorders, such as

bulimia and anorexia. Efforts should be put into identifying opportunities

for partnerships with the media and fashion industries that promote

positive body image.

41.9. Encouraging the private sector to increase its commitment

to health issues: making the industries involving potential risks

aware of their responsibilities through negotiation, fostering a

culture of corporate social responsibility; working with the food

and advertising industries to encourage the inclusion of key data,

facts and figures on non-communicable diseases and to improve the

nutrition environment, including production, supply and marketing

of food; making recommendations for reductions in levels of saturated

fat and added sugar and increased marketing of reduced/low saturated fat

and reduced/low/no sugar versions of certain food products; standards

for marketing, advertising and body image should be also explored;

advertising of harmful products should be banned.

41.10. Strengthening integration between care and prevention

by enlisting the support of health professionals: introducing health

education as a key element of initial and continuing medical training, including

in particular nutrition, health and human rights education; introducing

health literacy as a key indicator of good hospital care. This includes

a strong interest in the determinants of health and a reduction

in the routine and excessive use of medication which can be expensive,

pointless and/or harmful or even dangerous.

41.11. Promoting universal screening for risk factors at key

ages or in specific situations: facilitating family consultations

for the prevention of certain genetic or environmental risks; applying

cost-effective approaches for oral and dental disease prevention

and the early detection of breast and cervical cancer, diabetes,

hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors. Checks and disease

testing are still sadly patchy and biased to the more affluent areas:

a universal risk assessment and management programme could significantly

increase uptake of the preventative interventions and offer a real

opportunity to reduce health inequalities.

41.12. Dealing with the wider social setting that influence use

of alcohol, drugs and tobacco: addiction is often closely associated

with markers of social and economic disadvantage; policies need

to regulate availability through pricing and licensing, to inform

people about less harmful forms of use, to use health education

to reduce recruitment of young people and to provide effective treatment

services for addicts. Trying to shift the whole responsibility on

to the user is clearly an inadequate response. This blames the victim,

rather than addressing the complexities of the social circumstances

that generate legal or illegal drug use. Effective addiction policy

must therefore be supported by the broad framework of social and economic

policy.

41.13. Adopting appropriate measures to enable elderly persons

to lead independent lives: policies should enable the elderly to

choose their life-style freely and to continue to live in their

familiar surroundings for as long as they wish and are able to,

by means of the health care and the services necessitated by their

state. In the context of a right to adequate health care for elderly

persons, Article 23 of the (revised) European Social Charter calls

for the setting-up of health care programmes and services (in particular

nursing and domiciliary care) specifically aimed at the elderly.

In addition, there should be mental health programmes for any psychological

problems in respect of the elderly and adequate palliative care

services.

41.14. Devoting special attention to mental and psychic health:

this includes the promotion of well-being, the prevention of mental

disorders, the treatment and rehabilitation of people suffering

from such disorders, and the promotion of a culture of work-life

balance; the range of suicide prevention initiatives should be extended

particularly among young people, by opting for a more comprehensive

approach to mental health in its various components (biological,

psychological and social). A national mental health policy should

also involve the social integration of highly marginalised groups

such as refugees, disaster victims, the socially excluded, the mentally

disabled, very elderly and frail people, women and children suffering

violence and the very poor.

41.15. Formulating, implementing and periodically reviewing a

coherent national policy on occupational health and safety in consultation

with employers’ and workers’ organisations: building an effective infrastructure

of workplace health protection, with legal controls and power of

inspection; promoting the right to health at work and influencing

the prevention and reduction of risks at the workplace, which is also

a suitable place from many points of view for the prevention and

early detection of non-communicable diseases; encouraging access

to sport and an active lifestyle at the workplace; promoting workplaces

which are safe, healthy and ergonomically appropriate to reduce

the burden of musculoskeletal disorders.

41.16. Developing healthy transport policies and pedestrian/cyclist-friendly

towns, in co-operation with local and regional authorities: people’s

most immediate environment is critical for their health and well-being;

better public transport translates into less driving and more walking

and cycling; increasing financial support for public transport instead

of road building; introducing the “polluter pays” principle setting

tax to the pollution caused by the use of vehicles; changing land

use, such as converting road space into green spaces, increasing

bus and cycle lanes, encouraging in-town retail trade, instead of out-of-town

supermarkets.

41.17. 41.17. Encouraging the participation of civil society

organisations: patients’ and consumers’ associations, registered

charitable bodies and non-governmental and intergovernmental organisations can

help to disseminate information and raise awareness. In addition,

participation of patients, consumers, citizens in decisions regarding

their health is a key principle of a modern public health, which encourages

co-operation, negotiation and problem-solving.

41.18. Setting-up evaluation systems for prevention policies:

it is critical to measure the evolving situation and the results

with a view to reliable monitoring of the measures taken and their

effects on the basis of indicators developed by each country; standardised

data and information collection should be promoted, encouraging

standardisation of the relevant indicators for evaluation of these

policies.

6. Conclusions

42. Prevention is primarily a way of acting and a question

of attitude as much as of means. Governments can help through certain

measures to bring about changes in representations and mentalities,

create a social, economic and environmental context that encourages

health and pave the way for a disease prevention and health promotion

culture.

43. The rapporteur believes that tomorrow’s medicine will be about

looking through a new pair of glasses which reveal the true causes

of disease. In most cases these lie in faulty nutrition, pollution,

stress, negativity, addiction and lack of exercise – the greatest

cause of all being ignorance. The original meaning of the word “doctor”

is “teacher or learned man” and that is perhaps the most important

role a health professional can perform.

44. With the 2005 Warsaw Action Plan, the Council of Europe member

states agreed that protection of health as a social human right

is an essential condition for social cohesion and economic stability.

They supported the implementation of a strategic integrated approach

to health and health-related activities. Social support is an essential

determinant of health. The chief criterion for gauging the success

of health system reform remains effective access to health care

services, including disease prevention and health promotion, for

all, without discrimination, as an individual’s fundamental right.

45. The rapporteur considers that the health sector, which is

particularly characterised by powerful pharmaceutical lobbies and

is thus subject to market laws, only seldom questions the cost/benefit

ratio of advanced techniques, which are becoming ever more expensive.

It also suffers from the lack of importance attributed to patients’

organisations, NGOs and health professionals, who could make a valuable

contribution to prevention in terms of resources and human capital.

46. International data indicate that the cost/effectiveness ratio

of health care systems can be improved.

However,

it is not sufficient to reduce costs; it is also necessary to spend

money differently and to look at health policy from an overall perspective,

incorporating an ethical, social and human rights dimension in the

reforms to be undertaken.

47. In conclusion, it seems justified to recommend concerted and

concrete action in the field of prevention by Council of Europe

member states with the aim of allocating a minimum of 0.5% of GDP

to preventive health policies.

48. It would be also desirable to further strengthen the co-operation

between the Council of Europe and WHO on health matters, inasmuch

as the Council of Europe provides a parliamentary and civil society

platform for the wider Europe.

![]() from different horizons

have pooled their experiences in the field of prevention in healthcare. Their

findings and proposals are as follows:

from different horizons

have pooled their experiences in the field of prevention in healthcare. Their

findings and proposals are as follows: